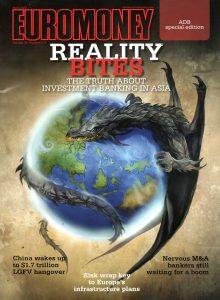

Reality bites: the truth about investment banking in Asia

Diving the Titanic

10 April, 2012AIG sale introduces world to passive global coordinator

10 April, 2012Asia is the future; that’s an article of faith in global investment banking. And there is no denying that Asia is where the growth economies are, the dynamic young populations, the most vibrant trends in trade and market development. But global bank HQs need to temper their expectations a little.

For all the promise of this region, investment bankers here face a host of challenges. Asian investment banking is unhealthily tilted towards equity capital markets, making it especially vulnerable to times – like the six months until early March – when those markets are closed. Within that, it’s far too focused on China, too. Competition from local houses is growing by the day; fees, already under pressure, are being sliced by an irksome trend of issuers putting as many as nine bookrunners on deals; and headcount costs are stubbornly high for good people at exactly the time that banks are being told by head office to slash bonuses.

See the article as it ran here: http://www.euromoney.com/Article/3005687/CurrentIssue/85141/Reality-bites-The-truth-about-investment-banking-in-Asia.html

A detailed study of revenue by Euromoney’s partner, Dealogic, allows us to paint the true picture about investment banking revenue in Asia.

It’s true that, over the last seven years, Asia’s contribution to investment banking revenue globally has grown, from 5% of the global pie in 2005 to a peak (so far) of 14% in 2010, before sliding back to 10% so far this year. It’s worth remembering, though, that the rising Asian percentage of global fee wallet really reflects the state of the rest of the world more than anything else: global fee revenue in 2011 was almost $10 billion lower than it was back in 2006. One need do little more than stand still in such an environment to shine.

It’s true, too, that Asian fee revenue has rebounded from the global financial crisis much faster than anywhere else – but it fell further along the way. US and European revenue figures peaked in 2007 and have never come very close to those levels since. Asia’s investment banking revenues halved in 2008 – a worse percentage fall than anywhere in the west – before their recovery.

But the bigger issue with Asia is just how heavily reliant on equity it is. “There isn’t a single person who doesn’t think ECM is the basic engine of profitability in investment banks in Asia,” says one of the region’s leading headhunters. “Look at the recent changes at Goldman,” he says, referring to the appointment of Dan Dees and Matthew Westerman as joint co-heads of ex-Japan Asia investment banking; both of them have ECM backgrounds. “When ECM markets are quiet, it’s a big problem for everybody.”

SUBHEAD Dissecting ECM

When markets are rolling, the dominance of ECM is just fine, and this is when Asia really does make a meaningful contribution to the global pie: 27% of global ECM revenue in 2010, a year in which it outpaced Europe by generating $5.6 billion of revenues. But the problem is, markets aren’t always rolling, and Asia – with relatively young and volatile markets, prone to fickle capital flight to the west – is vulnerable when it happens. Asian ECM revenue in 2008 didn’t even hit a billion for the entire street: the $973 million of fees represented a fourfold decline from the previous year.

“Asian markets are much more centred on ECM product, which is 70% of the street revenue opportunity,” says Matthew Hanning, head of investment banking, Asia Pacific, at UBS. “If you are very dependent on ECM and markets are difficult, then business is difficult.”

The picture varies from house to house. Based on public data available to Dealogic, some names do look particularly reliant on ECM. It accounted for 71% of Morgan Stanley’s revenue in 2010, and 64% in 2011, despite the new issue market shutting down halfway through the year. Goldman Sachs looks similar: 69% in 2010, 52% 2011. After that, the concentration gradually dilutes: UBS (65% 2010, 51% 2011), JP Morgan (64% 2010, 41% 2011), Deutsche Bank (58% 2010, 57% 2011), Credit Suisse (64% 2010, 41% 2011).

Why so high? “I don’t think that people focus on originating ECM activity because it’s a better fee pool and don’t focus on M&A or DCM,” says Hanning. “People chase what’s there.”

Dees at Goldman Sachs agrees. “I don’t think the reliance on ECM historically has been a misguided strategy for the street,” he says. “Because the other drivers of the banking business – debt capital markets, M&A and derivatives – were so nascent in their development, ECM was the dominant business. As a result, the business out here has risen and fallen based on the state of ECM in the past decade.

“Nobody had a strategy that isolated their whole business as ECM. It’s a function of market activity levels and the stage of DCM and M&A development.”

Intended or not, that’s what has happened. So with markets shut for months, how important is it that ECM comes back? “It’s vital. Vital,” says Rob Sivitilli, head of corporate finance and M&A for southeast Asia at JP Morgan, speaking before the AIG/AIA trade (see news https://www.chriswrightmedia.com/aig-sale/) gave a positive sign that markets were re-opening. “The ECM business makes up about 75% of the capital markets business in Asia, which in turn is two thirds of the region’s investment banking business.” Little surprise, then, that throughout the early months of this year, investment bankers have been looking with trepidation at the deals – mainly small, and mainly block trades – that have been testing the market. “What happens next in terms of this region’s IPO activity for the rest of the year is very dependent on executing some successful deals,” says Sivitilli.

Some banks talk about as many as 40 ECM deals ready to go in their pipelines, and they live in fear of somebody wrecking the market before it’s got going. As one banker puts it: “Some bonehead brings out a deal and it doesn’t go well, and it seizes up for everyone else.”

If banks are over-reliant on ECM, they are equally over-reliant on China. In 2011 China accounted for 54% of Asia ex-Japan investment banking revenue, a figure that has risen steadily over the years, from 29% in 2005. Within ECM, it is almost absurdly dominant: 70% of total Asia ECM revenue in 2010, and 66% in 2011. It also accounted for 67% of 2011 DCM fee revenue, and though less dominant, is increasingly the focal point of M&A as well.

Some say this is not so unusual. “It’s interesting to look around the emerging markets,” says Russell Julius, head of global banking, Asia Pacific at HSBC. “Everyone talks about Latin America’s promise, but Brazil is 80% of Latin America.” Similarly emerging Europe is dominated by Russia, the Middle East by Saudi Arabia and Africa by South Africa. “As an emerging market feature, where you’ve got to get right is a lot smaller than it used to be.”

But at a time when debate continues about how hard a landing China is facing, it’s not especially healthy to have such a concentration on one country.

SUBHEAD: Chasing the money

There must be a number of caveats to this data, though. To an extent, it’s natural that banks will go where the money goes: Morgan Stanley might have looked hopelessly lopsided in 2010 when only 29% of its investment banking fee revenue came from anything other than ECM, but it was also the top bank in Asia for overall revenue, pulling in $423 million. The banks behind it – JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, UBS, Credit Suisse – all got at least 60% of their money from ECM that year. And even though 2011 was nothing like as good a year for ECM as 2010, because of the market closing in the second half of the year, it’s still those same banks at the top in overall fee earnings. Of the top five (Goldman, Credit Suisse, UBS, Deutsche, Morgan Stanley) only Credit Suisse got less than half of its revenue from ECM.

Besides, looking at those same league tables, the more diversified approach might look healthier in percentage terms, but it doesn’t put them at the top in overall revenue. In 2010 HSBC’s nicely balanced split of fee revenue – 32% DCM, 27% ECM, 21% loans, 20% M&A – was only enough to rank it 16th in investment banking fees (having bolstered ECM, it moved up to seventh in 2011). Standard Chartered, similarly diversified, ranked 18th in 2010, and RBS – which has since ditched equities completely – 25th. Barclays, having not yet gone into equities by then, didn’t even make the table.

Still, the more pure-play investment banks are at pains to stress the diversification of their business. “Some banks are certainly highly leveraged to the equity business; for our part we have a very good balance between equity, M&A and other products,” says Kate Richdale, head of investment banking for Asia Pacific at Morgan Stanley. “When the IPO market is not firing on all cylinders, there is certainly an impact. But what we have seen is that other areas can make up the shortfall. Last year, when the IPO market slowed, our equity business shifted to focus on block deals.” Dees at Goldman – the other house most obviously linked with ECM – makes a similar claim. “We’ve always had an intention that our investment banking business in Asia would mirror the breadth and diversity of our investment banking business around the world,” he says. He argues it’s just a question of underlying securities markets maturing, driving issuance and therefore a more diverse range of investment banking work.

It’s also important to acknowledge that public deals aren’t the whole picture. “There are significant revenues in Asia away from what is publicly reported,” says Vikram Malhotra, co-head of investment banking for Asia Pacific at Credit Suisse. “There is a lot of work done with corporates which is part of investment banking but is undisclosed, because in certain cases you do a bilateral transaction. There are two buckets of revenue: the public and the private.”

At UBS, Hanning notes that ECM and China dominance simply reflects the evolution of a market. “It’s stage one of the privatisation of a country,” he says. State-owned enterprises and private enterprises form the IPO market and, since most start with 25% free floats, ample opportunity for secondaries when they need more capital. Widespread debt issuance, and M&A activity, tend to follow later, eventually shifting revenue composition. “Net net, the dominance of ECM revenue is probably going to come down,” says Malhotra. “ECM fees over time are going to be flattish, maybe slightly growing, but other fees will probably grow faster.”

SUBHEAD: New entrants, new departures

Be that as it may, the fact that new entrants are working their way into ECM reflects the fact that it is still seen as instrumental to fee revenue. The two obvious examples here are HSBC and Barclays, both of which, until recently, were best known in investment banking just for debt capital markets.

In 2009 a group of senior managers at HSBC, including Stuart Gulliver, Samir Assaf (head of global banking and markets) and Robin Phillips (who holds that role for Asia Pacific), “sat down and said that the equities business is something that we do need to be more relevant in,” says Phillips, prioritising certain markets like Hong Kong at first and ensuring that the secondary side was built alongside the primary.

HSBC has done this before and failed, at least twice, most obviously when it hired former Morgan Stanley man John Studzinski to build a global capital markets business in 2003; he was gone by 2006, and the ambitions too.

“If you contrast what we have done now with what happened in the early 2000s, the difference is that we had a step by step plan over a three to four year period, rather than a ‘let’s go out and hire hundreds of investment bankers and make it work’ approach,” Phillips says. “You can’t change clients’ perceptions overnight. But clearly for us the Asia piece was absolutely critical.”

Partly this was a consequence of a change in the way business beyond investment banking appears to be awarded. “We’ve seen an evolution in the way that flow business is awarded. For example with payments and cash management mandates – and this is very high quality business – increasingly the buying decisions there are being made by the C-suite. So we needed that access, to get the buying decisions in our favour around the overall platform.”

In the last year, there has been clear progress, particularly in Hong Kong, where the bank was a bookrunner on seven of the 10 biggest IPOs in the city all year, including the well regarded Sun Art Retail, and has got on some important M&A deals such as CKI’s purchase of Northumbria Water in the UK. Today, Phillips bristles at any suggestion that HSBC is not talked about in the market as a force in equity and M&A. “Well we should be coming up in conversation now, based on the deals and the rankings we achieved in 2001,” he says. “If you’d made that comment 12 months ago I would have understood it. Today the perception is changing.”

Barclays, too, has sought to build an equity presence, which has yet to tear up any trees but which its management present as well positioned, and well timed, for when recovery comes. “We’re especially strong on the debt and M&A side, with a deep and experienced M&A bench. Our equity business is slightly younger, but continues to make good progress” says Johan Leven, co-head of corporate finance, Asia Pacific at Barclays Capital. “In terms of our revenue mix, we were less exposed to the equity business last year than some other firms,” presumably including his previous house, Goldman Sachs.

Moving in precisely the other direction is RBS, as its sale of cash equities and equity research has also removed it from ECM and M&A – and not, in this region, with any obvious delight about the situation. “It’s somewhat disappointing from a parochial perspective, because we were doing quite well,” says John McCormick, chief executive, Asia Pacific. He’s right: last year RBS was on the Queensland Rail IPO, for example, the biggest in Australia all year; in M&A it was on the biggest trade into Asia last year, SABMiller’s purchase of Foster’s Group. “The platform was credible and growing. But it’s a global game, a team sport, and the decision was taken that we couldn’t make it profitable as a whole.”

“We took a tough decision to pick our battle,” says McCormick. “What we are doing now is really to play on our strength,” including significant businesses from DCM to convertibles and derivatives, in addition to in addition to the flow business like rates, fixed income and FX in the broader bank.

Putting a brave face on things, DCM bankers there say they prefer it this way. “From the debt side it’s not a bad thing,” says one. “We’ve been subsidising that business in a big way for years. It’s not good for institutional colleagues but for us, it means our capital is more focused on the business we feel we do well.” Unsurprisingly, people in this camp argue that Barclays had the model right originally and should have stuck with it.

But can that be true, given what we see about ECM’s power in fee numbers? While McCormick naturally has a position to defend – and not one he asked for – of life as a non-equity house, he makes an interesting point.

“The fee income coming from advisory work is not a whole hell of a lot, certainly when stacked up against traded products,” he says. “What people never talk to you about is the net income produced from those businesses. It is rare for an investment banker to talk about his business in terms of net income, post all costs, all indirect allocations, post bonus, post tax.” So just because you might get 3 or 4% fees on an IPO doesn’t mean you make money from it? “Well, it’s many years ago that it was 3 or 4%. ECM is a multiple of DCM but I’m not aware of many investment banks who are making money in fully loaded M&A and ECM in Asia at this point in time.” McCormick makes it clear just how hard it is to run a profitable ECM business in a tricky market, even in Australia, which is the part of the region where it was highest ranked. “Let’s not forget 2011 was the lowest fee year in seven in Australia. To run a global advisory business, you will need to have a big platform with a team of investment bankers at all levels, running around globally looking for opportunities, and the fees aren’t coming in the door… we couldn’t see a sustainable way to give it an acceptable rate of return and that would take us from 12th or 13th league table position globally now to top 10.”

It’s certainly true that working out the precise cost of an ECM business is very challenging. “We look at the ECM business in the context of the wider equities business, including sales, trading, research, capital markets; structuring, cash, prime and derivatives,” says Dixit Joshi, head of global markets equity for Asia at Deutsche Bank.

Similarly Julius at HSBC notes: “The trouble with defining the profitability of ECM is that the ECM business has the narrowest definition of costs – a dozen aggressive people making deals happen – and the very widest definition of revenues. For it to work you need research, banking settlement, roadshows, sales.” He says most firms split ECM revenue 50/50, half for distribution and research and half for execution and origination, with each party taking care of its own costs.

That being the case, is it too simple to say that ECM is essential because it its dominance of fee pools? “It isn’t that simple anymore,” says Julius. “It used to be.”

But however you cost it, it isn’t cheap. “An equity business is attractive, but an expensive business to run,” says Leven at Barclays Capital, who should know, having helped build one from scratch. “You need a big machine to do it and it’s an expensive machine to build with scale.” Debt transactions pay far lower – perhaps 20 basis points on an investment grade deal compared to as much as 4% on an IPO – but “there you have much more flow-orientated business.” (For a detailed study of Asian DCM, see our March edition.) “It’s much cheaper and quicker to execute debt deals for investment grade issuers than an IPO. If you work on an SOE in China, it can take two years before you get there. It’s a lot of resources for a very long time.”

M&A

Models vary for developing investment banking in Asia, but there are two common themes: boosting investment in M&A, and combining investment banking with ancillary businesses, particularly if there is a corporate bank to blend in.

“There’s a recognition that the reliance on the IPO business cannot last forever,” says Sivitilli. “When the music slows down you’d better have a diversified platform that includes M&A advice – which brings in all the ancillary business such as FX and markets – or you’re going to get caught with no fees.”

Hence M&A is one of the few areas where hiring is still taking place. “I don’t think anyone feels they have every single person they would love to have in M&A,” says one headhunter. Colin Banfield, for example, was hired from Nomura to build M&A at Citi; Jason Rynbeck brought a team across to Barclays Capital from ABN Amro; and HSBC brought George Davidson from London to head M&A in the region. “That doesn’t sound anything out of the ordinary: you would have thought you would have some to head M&A,” says Phillips. “But so many bankers in this part of the world, both country and sector, default to equity. Having someone who is thinking cross-border and wakes up in the morning worrying about M&A is particularly important.”

Lately this build-out has been slightly more in hope than chasing actual volumes. “The broad pick-up in M&A volumes you’ve tended to see out of previous crises hasn’t been as strong this time,” says Rynbeck at Barclays. But like all his peers, he’s hopeful. “Cross-border M&A is potentially very strong: there is a lot of liquidity in the region, domestic banks are in good shape, and Asian corporates are going to continue to feature reasonably prominently.” A relatively recent development is that Asia is a fixture in outbound M&A as much as inbound, and while there is continuing interest in Asian assets for foreign multinationals – Nestle buying Hsu Fu Chi, for example – it is just as interesting to watch Japanese consumer groups like Suntory and Asahi, or Indians like Reliance and Bharti, or any of a host of potential buyers from China, moving out into the west, particularly as distressed assets emerge in Europe. “There’s no question Asian buyers continue to be a very significant part of the buyside for transactions worldwide,” says Farhan Faruqui, global banking head Asia Pacific at Citi.

And M&A is not just about the deals themselves. It’s what else it leads to. “Barclays is traditionally a strong financing and risk management house,” says Rynbeck. “One of the reasons we developed our M&A platform was to build upon the strength of our existing client relationships, and enhance the breadth of the dialogue with clients. If the discussion with CEOs initiates at the strategic level, you naturally come in at an earlier point in the discussion, which means you are well established in any subsequent financing and risk discussions.”

Bankers love the extra work that comes with M&A. “If you’re talking about acquiring an entity, it’s a natural extension to talk about the funding of that trade,” says Hanning. “And if it’s covered for funding, the next discussion is from a risk management perspective. If you are crossing geographical boundaries, is there an FX risk for you? Is there an interest rate risk? They can be as important to our returns as working on the transaction.”

This view, on the face of it, works against the more pure-play investment banks, but they are enthusiastic too. “While some companies use commercial banks as M&A advisors because they provide a funding solution, the truth remains that clients still need the very best strategic advice, and work will always be there for the more specialist M&A houses with event funding expertise,” says Richdale at Morgan Stanley.

SUBHEAD: Models – it’s not just IB

Investment banking is never seen in isolation anymore. Deutsche was one of the leads on the AIA selldown by AIG. “Clearly that was a milestone investment banking transaction. But we quickly started looking at all the ancillary areas where our clients would need help,” says Joshi. “Who is taking down the stock, where are they going to get it financed, are we competitive on the financing and so forth. Six billion dollars of stock had to be placed. Some would be with people who needed financing, or who wanted to dispose of other stocks in their portfolio to make room for AIA, in which case we wanted to be able to say: send your trade our way.”

In Deutsche’s case, it’s a matter of meshing investment banking into the powerful markets business that is the bank’s true engine room in Asia and elsewhere. At other banks, the model is different again.

Citi integrated its corporate and investment banking businesses in 2009, and Faruqui now presents that unified approach as a point of difference. “We are positioning our business to be in the middle of the key flows with our clients whether it’s lending, derivatives, FX, interest rate products, M&A or capital markets,” he says. As one insider puts it: “a dollar in investment banking usually leads to 10 in corporate,” although equally it can flow the other way.

Citi, in fact, is one of the few places to have engaged in a significant build in recent years. Faruqui recalls the tail end of the crisis; “Hiring at that time was difficult because people either weren’t convinced or wanted to wait and see before making a decision to move,” he recalls. Not until the second half of 2010 did they start to arrive: Colin Banfield from Nomura, Gary Kuo from Barclays, Tony Osmond from Goldman, Rodney Tsang from BAML, Roger Zhu from CICC. “We didn’t overhire and we have not overbuilt,” he says. “We have demonstrated in the last 12 to 18 months that we can win and gain share.” He picks a good moment to make this claim: on the day of the interview, YTD league tables show Citi top in Asia Pacific ex-Japan ECM, second in announced M&A and third in G3 DCM.

JP Morgan has built a similar model based on synergies with asset management and corporate banking, both of which have been built heavily in Asia over the last 18 months. HSBC and Standard Chartered both have powerful corporate banking businesses and use the balance sheet where it helps, often in concert with investment banking.

Others are known for their particular skills. One rival banker refers to Credit Suisse as “like a super-boutique for Indonesia”, and it’s not intended as the insult it might seem: if there was ever a time to be known as an Indonesia specialist, it is surely now, when the country’s banks and corporates gear up for activity in issuance in the afterglow of the sovereign’s upgrade to investment grade. Helman Sitohang, the investment banking co-head, is Indonesian; also that Eric Varvel, the CEO of the investment bank globally, was once the Indonesia country head (as one rival banker says: “It helps to have a CEO who knows what Jakarta looks like right now”). Naturally, Credit Suisse argues that its Indonesian strength doesn’t mean it’s not equally proficient and active elsewhere in Asia.

Subhead: Fees

And what of fee pressure? Opinions vary. One senior MD, talking of DCM fees, describes them as “miserable. That hasn’t changed. It’s very, very low, way below where things would be in the US or Europe.”

This would certainly be a view shared by anyone doing business in India, whether on the debt or equity side; take a look at Coal India (Euromoney, December 2010), in which the six bookrunners of the US$3.46 billion IPO – the largest ever in India – got $34 between them, or ONGC (news section), which one very senior banker describes as “absolutely ridiculous. It doesn’t help the markets at all.”

Others disagree. “Fee compression is over, across the board,” says Sivitilli. “Banks are being much more disciplined.” He says JP Morgan recently walked away from an opportunity in which the client wanted to pay a lower rate; afterwards it found that several other international banks had done the same. “We’re seeing more understanding by clients, saying: we get it, we’re not trying to pinch for the last nickel. And in some cases, in M&A, I’m seeing fees moving up.” And not by a small amount: he thinks the premium on some deals relative to two years ago is 20 to 30%. Granted, M&A is the area with the greatest range of fee possibilities; buyside roles typically carry fixed fees, while sellside roles often involve incentive structures, for example. But he says the trend is clear.

Sivitilli puts this down to a change in the model for banks in Asia. “Many banks in Asia, for quite some time, were just focused on revenue,” he says. “But international banks, over the last two to three years, have migrated to a profits-based view. Most financial institutions in 2006 didn’t have a well-developed framework for assessing capital; shocking but true.” Headcount pressure has helped. “The discipline around hiring is driving discipline around fees.”

In ECM, Julius at HSBC thinks fees in Hong Kong at least are pretty good. “The good thing about the Asian business, especially in Hong Kong, is that it is the highest margin business because unlike anywhere else in the world with one or two exceptions, IPO fees in Hong Kong have the buyer and the seller paying: between 2 and 3% from the seller of equity, and 1% brokerage from the buyer.” Discretionary fees are becoming more common in ECM deals too.

But the big problem for bankers is not that fees themselves are falling, but that the number of ways the fees are split is increasing. The news story on AIA/AIG on page xxx discusses this in more detail, but generally in both ECM and DCM transactions it is becoming commonplace to see seven, eight or even nine bookrunners on one deal. This has led to some absurd titles such as – on AIG – the idea of a passive global coordinator. It splits fees among more bookrunners than was ever the case before, and isn’t healthy for the markets either, since it reduces accountability.

“One thing we’re seeing more of is multiple bookrunners on transactions, which wasn’t the case even 18 months ago,” says Richdale. “It does make things harder, but we are a differentiated bank providing differentiated service.”

Another, related problem is that as local players gain traction, the field is getting ever more crowded. “There are more and more players in the market,” says Julius. “Since Macquarie entered, you’ve also got the regional brokers like Haitong, Citic, Religare and Samsung [which has since dramatically scaled down its Hong Kong operations], then regional banks like DBS, OCBC and CIMB, and people who have bought other bits and pieces like Barclays and Nomura. That’s 10 new names.” Partly, this leads to the pressure to add more bookrunners. “There’s an intuitive grocer shop mentality towards bookrunners – ‘three or four for the price of one’ – but when it comes to actually managing the deal you can only have two or here. Otherwise there’s chaos and no responsibility.” And partly it adds to fee pressure.

“One difference we have here with other regions is that we have very strong local competitors,” says Sitohang at Credit Suisse. Korea has local champions, and China and India clearly do; Malaysia’s CIMB signaled its own regional ambitions with the purchase of many of RBS’s equity and corporate finance businesses (see op-ed); DBS is a strong regional player and the other Singaporeans are thriving too. “They will get stronger. The investment banking business in this region will grow, but locals will want a part of it too.”

Still, despite the challenges, one need only look at the region’s demographics to retrieve a sense of optimism. “Our expectation is that in the next two years we will see $3.7 trillion of GDP growth in Asia,” says Joshi. “I believe that we may see a multi-decade period of growth akin to post World War Two in the USA, when you had young companies being spawned to cater to new industries; existing companies becoming a lot later; and a capital market that had to develop and grow to meet their needs.” That’s what keeps people coming.

Box: China JVs

China’s domestic market is not just a matter of potential. It’s already arrived. Domestic corporate and government bonds combined have already become the second biggest domestic debt capital market in the world after the USA. The A-share market, too, though suffering a difficult year, is clearly a force.

For many years, foreign banks have sought to be part of this, which they can do by establishing joint ventures with local partners. Nine have been licensed so far.

To see how they’ve evolved, it is instructive to look at the first and the last. Putting aside the special cases of Morgan Stanley/CICC and CLSA’s venture with Fortune Securities, Goldman Sachs was really the test case for China JVs; its foundation in 2004 was structurally extremely complex, with two separate ventures, only one of which it legally has a stake in (it backed the other by funding a former employee to capitalize it and effectively hold it in trust on Goldman’s behalf); one holds underwriting businesses, the other research and broking. Those close to the structure at its foundation recall meeting 40 government ministers in 10 ministries to get it approved; these days a 33.3% foreign ownership in a JV, with the majority held by the local partners and a split of board seats between them, is the norm. Today local partners must be successful local houses, unlike the early days when Goldman effectively started from scratch and UBS (which followed in 2006) created a new securities company out of a flagging local brokerage called Beijing Securities.

Being first, and with this structure, Goldman has had time to integrate. “We manage the China business as part of our overall investment banking business,” says Dees. “We’ve tried to build one team which goes across Goldman Sachs and Goldman Sachs Gao Hua. What we’ve always wanted to avoid is having a domestic team and a separate international team. That to me would be a failure.”

But the more significant change has been the scope of business. Post-UBS, licences have been quite limited: domestic A-share and bond underwriting, and M&A advisory. In Goldman’s and UBS’s case, the permits included secondary trading, brokerage and research.

And this has proved crucial to the Goldman venture. There have been entire calendar years in which it has advised on no A-share or domestic bond issues at all. Since Goldman still leads in overall combined China ECM, it doesn’t much care; the venture itself makes most of its money out of secondary trading and commissions.

For newer ventures, that’s just not an option, and there are questions about how profitable – if at all – any of the ventures are. Comments about the JVs tend to be big on optimism and low on specifics. “The JV is doing well, the mandates are building up, there is a great team and we have good hopes for the JV,” says one investment banking head. And is it profitable? “I can’t comment on specifics.”

And they also tend to speak more in hope of knock-on effects of a China business than clear hope of profitability from the venture itself. Joshi at Deutsche, which launched a venture with Shaanxi Securities in 2009, says the A-share underwriting pipeline there is “deep, with a number of potential large deals coming.” But he is equally enthused about “the ancillary business we would like to develop in China,” in particular involvement over time in the rapidly developing futures market, the currency and rate products that can come out of the development of offshore RMB, or the development of ETFs. “Our JV is important for tapping A-share issuance, but we’re making sure we are focused on broader market structure developments in China as well.”

Similarly, the RBS venture – which will now become probably the only area where RBS is still involved in ECM, since that accounts for 90% of the venture’s business today – appeals to McCormick for reasons beyond the equity capital markets. “We are very keen to grow the fixed income component, our core area of expertise,” he says. “But as a global FX house, we see the RMB as hugely important. It will become a reserve currency, if it’s not already.” McCormick, too, has great hopes for futures business.

Still, investment banking fees are not bad domestically. Chris Laskowski, chief operating officer, global banking Asia Pacific at Citi, says that although large cap ECM fees in A-share issues are “tighter than Hong Kong”, on the SME side – in IPOs worth the equivalent of $50-150 million range – they can be as high as 5 to 7%. “It’s a very quirky market in that respect.”

DCM fees, says Faruqui, are “more attractive than the rest of the region. There is a huge surge in volumes in domestic issuance since the financial crisis dislocation. In the long term, this market has the potential to be as large as the US domestic market. You cannot possibly discount it at this point.”

And so to the latest venture: Citi Orient. It was a long time coming and there’s no doubt Citi needed it, for the same reason that everyone else – Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, Deutsche and the rest – needed one: because even if the venture itself doesn’t make money, it’s much easier to pitch if you can throw that domestic ability into the mix. Laskowski says the focus now is on getting the 1500 to 2000 SME relationships of the corporate bank looking at the IPO market, for example.

Asked what Citi learned from existing ventures, Farhan says: “It’s not about the agreements; it’s about the people. It’s about the partners on both sides of the table sharing a common vision and commitment to a successful partnership.”

And that’s a common lesson of the many ventures to date. As one banker puts it: “Some banks have thought they had the upper hand in a partnership. That’s irrelevant if the other guy isn’t listening to what you’re saying.”

BOX: The headhunter view

What do the region’s top headhunters think of the market? Not a great deal. The mood is not good following the bonus announcements of most banks in the early months of the year.

“While everyone intellectually understood their compensation was going to be coming down 30 to 40%, when people see the number on a piece of paper they tend to have a more visceral reaction than they thought they would,” says one. “While some are flat to last year, most are clearly down, and in most cases have a restricted deferred element to the compensation.

“Every banker is becoming a financial institution specialist and working out whether having 60% of their bonus in the stock of that bank is worthwhile.”

So who wins in that environment? “The large US money-centre banks are considered to be the best, with JP Morgan the standout because of its share price performance comparative to the street,” says one. People are newly optimistic about Citi in this respect, he says – since few feel its share price can get any worse – and always about Goldman Sachs, although “the question on everyone’s mind is how people make money now they’re no longer proprietary trading. They don’t have the answer but they know people will figure it out, and the people who figure it out first will probably be Goldman.”

Still, not everyone is convinced that there’s much upside in any bank stocks, arguing that price to book ratios – for US banks, currently between 0.9 and 1.1 times, typically – don’t make a compelling case for improvement.

In Europe, headhunters say Deutsche is the closest European equivalent in terms of its likelihood of recovery; “It’s always been a successful bank and the premier German bank, which is where the initiative lies.” UBS and Credit Suisse are still able to attract people, “but people don’t want to be at RBS or other UK banks, and certainly not French banks. They are very wary of any organization from an aggressively regulated environment.”

Headhunters also note the growing importance of institutions that have clear balance sheet liquidity, something that clearly benefits HSBC and Standard Chartered.

Headhunters say they don’t see much headcount reduction now, because as one puts it, “they did it all last year.” “Whether there’s another round would depend on the equity issuance market, I would think. But I can’t think of a single institution that didn’t trim last year.”