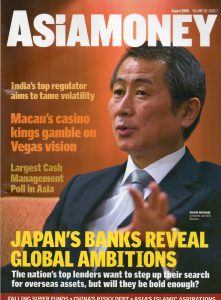

Kenichi Watanabe: Nomura’s global warchest

If an Islamic bank fails

1 August, 2008How to invest in active funds

1 August, 2008 Asiamoney, August 2008

Asiamoney, August 2008

There is a rumour doing the rounds that Nomura has amassed a war chest for acquisition: that the Japanese bank is so intent on realising its long-standing ambition to be a global force that it has built Y300 billion of funds to deploy on new purchases. Is that right?

No, says president and CEO Kenichi Watanabe. It’s actually Y500 billion.

Nomura has been mocked before for failing to deliver on its grand vision of being a global force. But one certainly can’t doubt its intent. At a time when global investment banks are being rocked by write-downs, Nomura – which had its own problems with sub-prime – sees opportunity, and Asia will be at the heart of it.

“I am very interested in looking at these assets [financial institutions that have become acquisition targets as a result of the credit crunch],” Watanabe tells Asiamoney. “We look at it from two angles. One is trying to capture capabilities we currently do not have, and the other is trying to capture a talented human resource pool. And, given that the US and European financial institutions have become more concerned about focusing on their core competencies, we are being shown offers. It is a very good chance to take advantage of the current environment.”

Watanabe will be selective about what comes up – he’s not interested in commercial banking assets, for example – and confirms Asia will be the focus of acquisitions. In time he would like the rest of the world to make up 30% of Nomura’s earnings, which, while not quite the heady level of 50% aimed for by Nomura’s top brass in the bubbly days of the early 1990s, would certainly be a step forward from the level today (since the bank had to take on significant write-downs in its US business, overseas operations strictly speaking accounted for a negative proportion of group earnings in the last financial year).

But stop us if you’ve heard this before. One Nomura leader after another has come in hoping to succeed where others have failed. Indeed, it is argued by some that Noboyuki Koga, Watanabe’s predecessor in the top job, stepped down to take responsibility for failing to diversify away from its dependence on Japan. There’s no questioning its force in Japan – Y72.2 trillion in domestic retail client assets alone, a figure Watanabe wants to turn into Y110 trillion in three years – but translating it overseas has been consistently challenging. What is the new man, installed this year, going to do differently?

Upon arrival Watanabe made a grand statement to Nomura’s shareholders and customers, and you can still find it prominently displayed on the Nomura website. “I intend to shift Nomura Group’s approach away from merely responding to the changing market environment to focus more on creating change ourselves.”

But what does this mean? “Usually when you look at the corporate leadership of multinationals and Japanese companies, they would normally say they adjust their business according to the changing business environment,” he says. “My ambitious tone in that statement was to be more aggressive: a proactive stance where we aim to create change ourselves.”

Watanabe intends to start creating that change in Asia. “Nomura was born in Asia, its roots are here. In Japan Nomura was able to be part of creating change, within the capital markets, the financial markets, and in regulations. And as a result Nomura went from a minor to a major company. Now, in Asia, the economies and financial markets are changing and evolving, and Nomura would like to be part of that change, and to promote it. Nomura can grow alongside its clients in these countries.”

Watanabe is speaking to Asiamoney on the edges of the Asia Equity Forum the bank has held in Singapore for five years, and considers the event to be an example of trying to engage directly in Asian market growth. Asia is clearly, increasingly, a focal point: even with a 400-strong cut in US headcount already announced, Watanabe acknowledges that “we ourselves have limited managerial or corporate resources” and so will have to be focused. “Rather than looking at the global investment banks who have been betting on everywhere and hoping that one of them goes well, we will be focusing towards Asia.” Plenty is happening in the region: a new corporate advisory business was launched in Shanghai this year, and in the Middle East Nomura this year became the first Asian bank to receive a licence from Saudi Arabia’s Capital Markets Authority.

Watanabe has clearly realised Nomura can’t do this organically, hence the interest in acquisition. This underpins measures like the recent issuance of Y120 billion in subordinated bonds, and the borrowing of subordinated loans from other Japanese financial institutions. He is keen to distinguish the recent capital raising efforts from those raised by US banks simply to stay solvent. “The capital we have raised so far is something we intend to use for growth rather than replacing [losses]…If the opportunities do exist, we are ready to use that buffer of Y500 billion for the growth opportunities we deem fit for our strategy.”

Y500 billion goes a lot further these days than it used to, both because of the declining value of potential acquisitions, and the relative strength of the yen against the dollar. But for Nomura to do what it really wants to, will it be enough? “Currently, we think the amount we’ve raised so far is appropriate for what we are seeing,” he says.”

But what makes Nomura’s ambitions particularly striking is the fact that the bank is in a pretty average state today. It logged a Y67.8 billion net loss in the 2007-8 financial year (although one can make a case to say that US GAAP accounting makes things look worse than they are, since they require the consolidation of private equity investee companies), with net revenue down 27.8% year on year (to Y737.3 billion). That doesn’t seem a particularly strong base to build from.

But Watanabe has actually been startlingly specific about what he wants to change, and the quantum he wants it to change by. The most strident example of this is in the global markets business, which many see as emblematic of Nomura’s failure to grow overseas in the way it had planned to. This division made losses in 2007-8, hit by the global credit crunch. Yet Watanabe wants this division to be generating Y200 billion of pre-tax income within three years. Bullet points on investor presentations call for a “top class fixed income house in Japan and Asia”, “tier one in Asian equities”, with a strong asset finance business besides. How?

“I think the figure of Y200 billion is ambitious, looking at where the market is right now,” Watanabe admits. “But although global markets had to make the losses because of market conditions, we also instructed global markets to try and recover what they lost through the markets as well. That’s one reason we thought the figure was appropriate, to push them to go.” Also, he sees opportunity in broadening the range of this business through fixed income and equity products (today it is seen as heavily reliant on structured bonds), and expresses an interest in moving into distressed assets. “This is an area where we want to try to learn more on how to value such assets. If we were able to do these things we think the Y200 billion no longer looks quite that ambitious.”

Across the board, there are similarly high hopes. At the same time as building a global competitive financial services group, Watanabe is demanding an average consolidated return on equity of 10 to 15% in the medium term. It can look a little too good to be true.

Watanabe has implemented some structural shifts in the bank, changing the top management structure so that there is a much higher responsibility for risk management. “Rather than just measure risk, we would like to try to apply management methods where we try to anticipate risk… It’s the CEO and COO’s role now to try to make sure we can predict risks.”

It’s natural this should be the case after the bank’s troubles in the US, in which it painfully exited RMBS business. He is almost alarmingly honest about what happened. “From a credit risk perspective, we didn’t really see the problems,” he says. “If you just look at the figures you can’t really see the story behind it. One example was subprime, where we did not know that the overall hurdle for people to be able to borrow money to buy homes in the US was low. That’s something that we did not know about.” The medicine for this business has been bitter indeed: as a result of the exit from the US RMBS business, Nomura booked losses of around Y73 billion in the second quarter of 2007-8 alone, and RMBS 140billion in the first half. Residential mortgage exposure was Y266 billion as recently as June 2007; it’s now all but gone. Headcount, outside of the asset management and Instinet businesses, is in the process of being halved, with overall cuts of 400 people, net. Several executive officers took 30% pay cuts for a year in penance.

That suggests a less risky business for the future. “One of the things we’ve tried to do, but maybe failed, is a quite highly leveraged business. The US investment banks have been leveraging off their balance sheets and making huge profits. Now, rather than that, we are trying to apply less leverage, although we will continue to offer derivative and structured products for our clients.” He speaks of client facing businesses replacing some of the proprietary positions the bank has traditionally used to make its money.

But this, too, makes it trickier to see just where the hoped-for huge growth is going to come from in Nomura. If there’s less leverage, and less proprietary activity, then where else? Nomura Merchant Banking, which includes the private equity activities that have made headlines in Europe over the years with acquisitions such as British pub chains, does not appear to be ready for expansion. “Given the current limited resources that we have, to try to expand our global merchant banking just outright is very risky,” he says, stressing the selective nature of the business (although nevertheless the Nomura business plan calls for a global portfolio of Y300 billion in three years ex-its investment in Terra Firma, with a constant pre tax income between Y30 and 40 billion a year). Investment banking was heavily down year on year in 2007-8, though it did turn a profit, Watanabe expects this to turn into net revenues of Y120 billion in three years; asset management is an area of increasing strength, but chiefly domestically. Here, too, expectations are big: Y43 trillion under management in three years, generating Y55 billion in pre-tax income. (That pitch-book again: “World-class player with strong investment capabilities in Japan and Asia.”)

Talking with Watanabe, it becomes increasingly clear just how key the human resources issue is to Nomura. He recognises it as a key rationale for any takeover: not just the assets and the franchise but perhaps more than anything the people. He asks with a smile if Asiamoney knows anyone who’s looking for banking work; then he asks again. The plan for the Asian arm of the investment banking division alone calls for an additional 50 people. And one might argue that Japanese institutions struggle more than some others in trying to integrate a global workforce into a single group. There’s also remuneration: until recently, the bank has not had a reputation for playing top dollar among international investment banks.

Watanabe is interested in this observation, wondering what we’ve heard. But he acknowledges: “There were certain people in Nomura that felt that they were not being compensated enough for the efforts they put in. We are trying to install proper managerial systems to make sure appraisals are done in a way that compensates people properly.” He speaks of the importance of “creating a much wider human resource pool within Nomura which can be utilised on an international basis.” He feels that in his previous role running Nomura’s domestic retail operations he did effect change, over three to four years, and believes he can do so across the group.

In closing, how confident is that he can realise the vision he has for Nomura? “I think the fact that I am giving this interview backs the fact that we are confident,” he says. He mentions Goldman Sachs, Deutsche and HSBC as examples of banks that, while globally active, still have specific home markets of unquestioned strength, and says he hopes Nomura can do the same. “Given our roots, and the fact that we were born in Asia, we are willing to try to make Asia the centre for our expansion.”