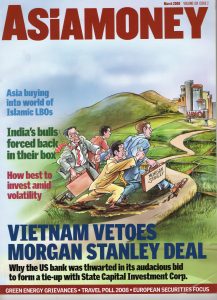

Vietnam vetoes Morgan Stanley deal

Malaysia hopes Ninth Five Year Plan will insulate it from global downturn

1 March, 2008Vietnam banking a crowded sector

1 March, 2008

Asiamoney, March 2008

Morgan Stanley announced a new joint venture in Vietnam in February: a landmark, the first of its kind. But it wasn’t the venture everyone was expecting. That one had been canned weeks earlier, in a turn of events that says a lot about the competitiveness of foreign investment banks trying to get a foothold in one of the world’s most vibrant frontier markets.

canned weeks earlier, in a turn of events that says a lot about the competitiveness of foreign investment banks trying to get a foothold in one of the world’s most vibrant frontier markets.

What Morgan Stanley announced on February 13 was a joint venture with a local firm called Gateway Securities, a Hanoi-based brokerage and investment banking outfit. Morgan Stanley will hold 49% of the venture, which among other things will be able to conduct underwriting, advisory, brokerage, research and principal investing.

It’s an interesting deal, for sure. Gateway is no household name in Vietnam, but that’s hardly the point: it’s the licence that really matters here. “They’ve bought a stake in a licence, they haven’t bought a licence in a firm,” says one observer. “It’s good business for Morgan Stanley: it’s a call option on Vietnam,” says another. “If everything falls apart they can walk away without losing much money. If it takes off, they’ve got the licence to benefit.” Morgan Stanley is believed to like the idea of building a clean new business, without legacy or politics; it is the first time a Western firm has bought a stake in a Vietnamese brokerage. What’s more, the cost is believed to be in the low tens of millions of dollars, a pittance by Morgan’s standards.

But it’s not the deal Morgan Stanley was had been expected to complete – which would have been a good deal more interesting, influential and lucrative. Last March 19, the bank had announced plans to establish a securities firm with State Capital Investment Corporation – the closest thing Vietnam has to a sovereign wealth fund, and entrusted with the control and restructuring of the country’s state-owned companies (which, in a Communist country, is most of them). SCIC Morgan Stanley Securities, once its domestic licences were in place, had been expected to start operations in the fourth quarter of 2007.

What a deal this would have been. SCIC today has control of 833 companies, and is mandated to decide what to do with them: divest them, list them, sell them domestically or internationally. It has been closely modelled on Temasek and Khazanah, the investment arms of the Singaporean and Malaysian states respectively, and in due course is expected to have responsibility for investing the nation’s reserves too. In a country which has beaten 8% economic growth for each of the last three years, newly admitted to WTO and with 85 million people who are only just discovering banks and consumerism, what better partner could there be to form a joint venture with?

And that, really, was the problem: the deal was just too good to be true. “One can understand the enthusiasm of both sides but they overlooked a rather obvious stumbling block, which is that in that position [SCIC’s] you have to be extremely careful if you are setting up a business in competition with those people who would be your major service providers,” says Dominic Scriven, director of Dragon Capital, one of the country’s longest standing investment firms. “I think the problem in SCIC is that at this early stage of its existence, it is simply so large an institution that it has to be focused on that, rather than on a more diversified set of financial services.”

Those close to the deal say the writing was already on the wall by the middle of last year. And then on January 1 SCIC’s whole leadership changed. Chairwoman Le Thi Bang Tam, who in November had given the keynote address at Morgan Stanley’s annual Asia Pacific summit at Singapore’s Mandarin Oriental, was replaced by minister of finance Vu Van Ninh as chairman, with his deputy Tran Van Ta as CEO. This ended any chance of the deal’s redemption, and in February an SCIC spokesman confirmed the deal was scrapped.

But what’s really striking is why it was scrapped. It wasn’t because of an objection elsewhere in Vietnam’s public sector apparatus, which can after all be labyrinthine, with different ministries and agencies often appearing to have overlapping responsibilities in the financial world. Instead, it was because of the carping of other investment bankers.

“Morgan Stanley and SCIC did sign the agreement for the JV,” says one well-placed observer. “But then they had a lot of resistance, from various sources but mainly from other international investment banks. They complained: ’you cannot be a player in the market and a referee at the same time’.

“You cannot have an investment banking or securities company owned by SCIC, which is also the direct representative of the government owning shares in Vietcombank, Bao Viet and so forth. You have a conflict of interest: you would definitely give the mandate to the investment bank you have a joint venture with. And that’s how the thing got scrapped.”

Another adds: “It was nothing to do with politics. It was other investment banks explaining to the government the implications of this JV. Every Joe Blow on the street was doing it: every time they saw the Ministry of Finance or the State Bank they just kept hitting the same points, all the time, until the government said: well, you must be right.”

(SCIC’s deputy director general, Le Song Lai, responded in writing to Asiamoney’s queries. On Morgan Stanley he said only: “Although the planned JV between SCIC and Morgan Stanley did not go through as scheduled due to some reasons, we do still find each other good partners. Given the growth potential of Vietnam’s economy, there are plenty of other promising opportunities that we could do together.”)

In one sense Morgan Stanley was perhaps naive in ever expecting such a steal of a deal to go through, although nobody in the industry is blaming them for trying. But the fact that the weight of momentum against the deal – a signed, announced, confirmed deal authorised at the highest levels of the Vietnamese government –came from rivals is perhaps an indication of the ferocity of competition among foreign investment banks.

In mainstream banking, there’s no shortage of opportunities: only 10% of the country has a bank account and economic growth is beaten only by China. It’s little wonder that long-standing fixtures like HSBC, Standard Chartered and ANZ have applied for local incorporation in order to be more deeply engaged with the country and its consumers. For principal investment, too, possibilities abound. But in investment banking, the opportunities are nothing like as clear.

They should be; indeed, they’ve long been expected to be. In late 2006, many well-informed observers of Vietnam were confidently expecting as many as seven listings of landmark state-owned companies, at a value of a billion dollars apiece or more, in the following 12 months. This was supposed to be the tipping point, when the markets had enough securities of sufficient size and depth for global institutional investors to pay greater attention to the country; and when the advisory and (in time) overseas underwriting mandates for foreign investment banks would begin to repay the considerable effort invested in the place over recent years.