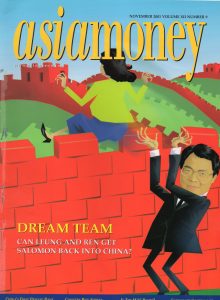

Can Leung and Ren get Salomon back into China? Asiamoney, November 2001

Asiamoney, cover story, November 2001

Salomon Smith Barney has spent big – symbolically big – on two established dealmakers in an attempt to push itself in to the top tier of China investment banking after two  years in the wilderness. Do Francis Leung and Margaret Ren have what it takes to rebuild Salomon’s bridges? By Chris Wright.

years in the wilderness. Do Francis Leung and Margaret Ren have what it takes to rebuild Salomon’s bridges? By Chris Wright.

“Listen! This is the sound of me turning the pages of my diary, rrrrrrippping out the appointments that might otherwise keep us apart. I shall have finished my 18 holes of golf by 9.30 am and shall be honoured to meet you thereafter.”

There is only one person on earth who can come out with this sort of boisterous flannel in arranging a time for an interview, and it is Ranjan Marwah, the effervescent headhunter who runs Executive Access in Hong Kong. But on the day Asiamoney calls for a chat he has even more reason than usual to be full of beans. Marwah has just concluded the placement, his own idea, of two of the region’s most celebrated bankers to one of the world’s most powerful banks. Leaving aside the multi-million dollar fee he is rumoured to have received in the process (“we have consistently been the most expensive search firm in town and nothing has changed”), his placement has the potential to change the dynamics of Greater China investment banking.

In July, Francis Leung left BNP Paribas Peregrine to become the managing director and chairman for Salomon Smith Barney in Asia, followed in October by Margaret Ren from Bear Stearns, who becomes head of China investment banking. These are people who occupy that peculiar hinterland of the financial vocabulary which seems more appropriate to the World Wrestling Federation than investment banking: they are ‘big game hunters’, ‘rainmakers’, hunting for ‘elephants’. They are pricey hires, among the priciest we have ever heard of, but at stake is the rehabilitation of Salomon in what is by far the region’s most important market.

The need for rescue

The reason Salomon has needed to spend, and spend big, is well-known. Salomon won’t thank us for revisiting it, but it sets a necessary context to what has happened since.

There was a time when Salomon Smith Barney was a fairly big thing in China. It hadn’t led real landmarks – a US listing for Qingling Motors through the pre-merger Smith Barney in 1994, a Salomon Brothers’ joint lead role in a Hong Kong dollar issue for Cosco Pacific in 1997, followed by another for Great Wall Technology in July 1999 – but that looked set to change when it was mandated to lead manage the privatization of CNOOC, considered the strongest of China’s three oil majors. This should have been a showcase for the power of Chinese names in the international capital markets. But the 1999 deal, originally mooted to raise up to US$2.5 billion, was pulled on the back of falling markets and weak demand. Although the behaviour of a volatile market was out of the bank’s hands, many felt Salomon had tried to price the deal too highly, and the displeasure at the failure was said to have gone as high as Zhu Rongji. In the aftermath, Merrill Lynch was added to the underwriting team, then CSFB, and when the deal returned to the market earlier this year Salomon had been removed outright. It hasn’t appeared on a China equity deal since, and appeared to have been ostracized from China mandates.

Last year was painful indeed, as the bank looked on while its competitors, particularly Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, took the fees and the prestige of one monstrous equity issue after another from the mainland: Petrochina, Sinopec, Unicom, China Mobile. In Hong Kong, the MTR privatization and, earlier, the Tracker fund sale were completed without Salomon involvement. And this is just the start. Many banks speak of China business occupying more than half of their expected activity in the Asian capital markets in coming years. To miss out on it would be more than depressing; it would be genuinely economically damaging. And people took notice. “What do you think’s going to happen?” a senior figure at a major international bank asked Asiamoney earlier this year. “You can’t tell me [Citigroup CEO] Sandy Weill is just going to sit there and say: fine, let the other US banks have all the China mandates and all the fees that go with them. They must be about to do something.” He was right.

The China team that had, fairly or otherwise, found itself shouldering much of the blame for the CNOOC fiasco moved on earlier this year when Guocang Huan and his team left for HSBC. There had been a difference of opinion on what to do next. “After CNOOC it was very clear that our reputation and our franchise in China had been damaged, and it was equally clear to me that the status quo was not sufficient to help dig our way out of that position,” says William Mills, managing director and CEO for Asia at Salomon. Mills wanted to bring in senior hires while keeping Huan in the group, he says; Huan didn’t like the sound of that and left of his own accord. It might have been for the best in both directions. Huan’s own reputation will be bolstered to an extent if the rumours that HSBC has a role on the Air China privatization prove to be true. And from Salomon’s point of view, Huan’s departure presented the opportunity for a clean break. But where does one go to start rebuilding? Who do you call in order to fight your way back into the arcane world of major China mandates?

Ranjan Marwah thought he knew exactly who to call, and he did: Francis Leung.

Cult of personality

When Leung rejoined Salomon on July 1, he was in fact returning to the Citigroup fold after an absence of 13 years. It probably didn’t much resemble the Citibank he left in 1988, but then, he doesn’t much resemble the person who left in 1988. You could argue that almost as much has happened to Francis Leung in the intervening period as has happened to Citi. He’s certainly made at least as many headlines.

More or less every major touchstone moment of Greater China finance in the last decade has involved Leung. The foundation, rise and collapse of the first and only truly Asian investment bank, Peregrine? Leung was the co-founder with Philip Tose (and the only director to escape censure in the report into its failure). The rise and fall of the red chip market? Leung led a stack of the IPOs, culminating in the astonishing 1,276-times oversubscription of the listing for Beijing Enterprises – the archetypal red chip for which the problems of valuation were complicated by its management of a toll road, department store, hotel, McDonald’s franchise and the tourism rights for the Great Wall of China. He became known as the father of red chips, a moniker he welcomed less when the whole market collapsed. Pacific Century CyberWorks? Leung is said to have taken two hours to raise a billion dollars in funding for the company and was instrumental in its back door listing in 1999, playing his part in the most remarkable corporate finance story of last year. The tech stock boom? Leung helped BNP Paribas Peregrine all but corner the market in new issuance, although many of them crashed dramatically after launch and one, Tom.com, caused near-riots and was criticized in Legco by SFC chairman Andrew Sheng (but does remain above its issue price, almost uniquely among the dot coms). Leung has been called the most significant corporate financier in Asia, and if that sounds bombastic, see who else you can think of who deserves the title, then call us. We’d love to meet them.

Leung is famous first and foremost for his contacts. He knows everyone. Everyone knows him. At Cheung Kong’s AGM this year, Li Ka-Shing told a press conference: “He is a personal friend and a rare talent. Our company will continue to do business with him.” (Li went on to remind Leung that he owed him dim sum in the near future. Shortly after that, Citibank, unusually, was made joint lead alongside Sumitomo on a HK$5 billion loan for Cheung Kong.)

In addition, he is widely liked. His background is not wealthy and he pushed his way to the top through sheer, relentless hard work. Yet, a regular churchgoer, he doesn’t strike you as tough. “Of all senior bankers I’ve worked with, he was totally without ego,” says a former colleague from Peregrine. “He just got on with it and worked hard.” Many from that era recall that they found him easier to deal with than the more arrogant Philip Tose; Leung just got on with his job and made a lot of money, handling as much as 35% of the capital raising for Chinese companies in Hong Kong up to late 1997.

Leung traveled the region, particularly China, pressing the flesh, improving his contacts, serving clients, and in the red-chip boom brought in deals for Peregrine from all over the country: Shanghai Petrochemical, CITIC Pacific, Beijing Enterprises, China Merchants, Guangdong Kelon. “He spoke terrible Mandarin, with a heavy Cantonese accent,” recalls a colleague from the Peregrine days. “But nobody minded. They appreciated the effort.” And though Peregrine was to fail, and the red chip market fall, clients remember him fondly for his devotion to them. “If I have a piece of business, I will give it to them,” says a senior executive at a Hong Kong company. “I think they’ve built a dream team there.”

There is a flip-side to this devotion to clients, of course. Many who have bought deals originated by Leung and his teams have lost a lot of money, first in the red-chip crash and secondly in the tech stock crash, in which BNP Paribas Peregrine was connected with many of the worst-performing new issues anywhere in Asia, among them Techpacific.com, Hongkong.com, iSteelAsia, and weak placements for PCCW and Citic Pacific. Of course, companies like this have plummeted all over the world, and there are examples (the initial PCCW placing, Tom.com) of Leung-led deals that remain above issue price; Leung advocates a buyer-beware attitude and argues that he has never launched a deal for a company that has then folded. The fact that red chips and tech stocks bubbled and burst, he argues, is not really his fault. Nonetheless, he has been associated with more of them than anyone.

One moment of timing that caught the market’s attention was Richard Farrant’s report on the collapse of Peregrine, which was made public earlier this year, and shortly before the announcement of Leung’s appointment. Clearly, discussions were underway beforehand (Marwah says negotiations took about 100 days and that the report came out after Salomon’s offer was made; Leung recalls first being called by Marwah, setting the whole process in motion, late last year), but many have assumed that Citigroup was waiting on the outcome of the report before making the hire. Mills denies this. “Its release was timely from our perspective but we were well down the road with Francis before it was released,” he says. “As you can imagine with a high profile hiring, we were in the process of conducting very thorough due diligence. From that we were very comfortable in terms of pursuing Francis, so we never really thought about it as a precondition.” Actually, the due diligence can’t have been that difficult: Leung himself had seen a draft of the parts of the report that referred to him well before it was ever published, so knew exactly what was coming. In fact the exoneration was explicitly stated, remarkably so for a deputy chairman of a failed bank: “I have no criticisms of Francis Leung’s performance as a director (and deputy chairman) of PIHL [Peregrine Investments Holdings Limited]”, wrote Farrant.

Whatever the significance of the Peregrine report, the deal was struck, with an official start date of July 1 and mind-bogglingly high remuneration. A popular rumour speaks of a guaranteed US$8 million per year over the next two-and-a-half to three years, and an informed source puts it even higher, speaking of a “comfortable eight figures annually”. Salomon and Marwah decline to comment, although Marwah does say this much: “All I am prepared to confirm to you is that he is the best investment banker in Asia Pacific, and his remuneration is absolutely reflective of that.”