Discovery Channel Magazine: Deepest Man

Discovery Channel Magazine, June 2010

It is January 23 1960, and Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard are on top of a wonky submersible called the Trieste, pitching on 12-foot Pacific Ocean waves having just made history. Over the previous nine hours they have piloted their craft, called a bathyscaph, more than seven miles to the floor of Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench – the deepest place in the world’s oceans. And now, waiting to be picked up by their support ships, they are already wondering who will follow them. “We thought that in a year or so there’d be more people out here with better machines, to explore these deep trenches,” Walsh says. “We certainly hoped so.”

Not so. Fifty years on, nobody has ever gone back; and since the death of scientist Jacques Piccard in 2006, Walsh – recalling the tale to Discovery Channel Magazine at his ranch in Dora, Oregon – is now the only man alive to have gone so deep. You might think of him as the Hillary of the ocean, except it’s even more pioneering than that: where hundreds have followed Hillary and Tenzing to the top of the world, none have ever followed Walsh and Piccard to the bottom.

This is the version filed. To see the article is it ran in Discovery, click here Trieste (3)

The journey really started for Walsh in 1958 when, as a submarine lieutenant, he volunteered to work on a program leased by the US Navy from a family of Swiss scientists called the Piccards. They had a submersible called the Trieste, an ungainly contraption comprising a thick-walled spherical cabin for crew suspended beneath a thin metal float filled with gasoline. “It looked like an explosion in a boiler factory,” Walsh thought on first sighting it. “I thought to myself: I will never get into that thing.”

The Trieste’s premise was simple: vent the ballast tanks to sink; slow or stop the descent by releasing solid weights filled with small steel pellets; and then, because the gasoline in the float is lighter than the water around it, return to the surface. The sphere itself, which would have to protect the crew from pressure 1,100 times greater than at the surface, was made of three rings, five to seven inches thick and glued together with epoxy at the joints. Walsh recalls the Admiral who ran the Navy’s Bureau of Ships coming to see the Trieste and asking how it was fastened together. Walsh told him about the glue. “Lieutenant Walsh, the Navy does not glue its ships together,” he replied.

But a glue-held submersible was in the spirit of the time, the Space Race era in which vast natural challenges were tackled with simple ingenuity. When the Trieste came back from one of its many test dives near Guam with failed glue joints caused by the differences in sea temperatures during the dive, Walsh says the team’s machinist fixed the problem with “a forklift truck and a large timber battering ram to put the pieces into alignment,” holding them together with a series of bands. “It was a remarkable piece of shade tree engineering and it saved the project,” Walsh says. Set against that, though, was a growing reluctance on the part of the Navy to court publicity, something he had to tackle when seeking approval for the record dive from Admiral Arleigh Burke. “The navy in its exuberance had claimed we were going to put the first earth orbiting satellite up. And they’d fire these rockets out of Cape Canaveral and they’d splash into the bay or they’d have to destruct them because they were heading for Kansas City. It was very embarrassing.” Consequently Walsh was told to garner no publicity: it would be promoted only after it was successful. “You tell [lieutenant Larry] Schumacher [who would be topside on Walsh’s dive], if he doesn’t come back up with Walsh, I’m going to have his balls,” Burke told Walsh.

After a series of tests in San Diego and later Guam, the stage was set. So on January 19 Walsh and most of his team set off in a corvette to the dive site and set about trying to find the deepest point by dropping dynamite into the ocean and timing the echoes. “We didn’t know exactly where the deepest place was: there were no maps or charts,” he says. “We didn’t care about exact depth measurement, only that 14 seconds was deeper than 12 seconds.”

At the same time a navy tug pulled the bathyscaphe towards the dive site at five knots. It arrived on dive day, January 23, in “a pretty good sea state, six or seven on the Beaufort scale.” For a craft like the Trieste, that was a challenge, but Walsh said they never considered aborting; “If we’d towed it back in, our masters in San Diego would have said: that’s it.” In fact, they did exactly that, but fortunately by the time the message reached them the Trieste had already dived. “The chief scientist put it in his pocket, walked around for a while, then sent a message back to San Diego saying ‘Trieste passing 20,000 feet’.”

Walsh and Piccard were together in the snug sphere for nine hours. “It was close. Jacques was two metres in altitude, and we had all our kit – equipment, instruments, cameras and stuff. We kind of coiled up inside it.” It got cold, too. “But, shit, it’s no more crowded than sitting back in peasant class on a trans-Pacific flight for 14 hours. You want to know about discomfort, just fly from here to Singapore.”

The Trieste began descending at 8.30 am and hit its first obstacle when it started bouncing along on the top of a thermocline at about 300 feet under. Eventually Piccard and Walsh valved off enough gasoline to break through and began sinking in earnest. It took five hours to get down.

It was dull in the main, but enlivened considerably at 31,000 feet. “We heard and felt a giant bang.” All instruments looked fine – so, despite being in a craft untested at this depth, deeper than any man had gone before, and having heard an explosion, they carried on. “We didn’t think it was OK to carry on,” retorts Walsh when challenged on this. “We knew it was OK to carry on because our readings were normal.” A pragmatist, he claims never to have been scared because the testing had been so rigorous.

The Trieste sank further and further, deeper than they had expected, until finally the loom of the lights was visible reflecting from the floor. Piccard ditched more shot to slow the descent and they made an easy landing; the gauge (wrongly, it would later turn out) read 37,800 feet. But this was to be no “giant-leap-for-mankind” moment. “We shook hands, congratulated each other and called topside on the underwater telephone, a voice modulated sonar. We told Larry Schumacher we had reached the bottom, 6,000 fathoms, and it was good.” What did he reply? “He just acknowledged. You kept your messages pretty simple.”

There, seven miles down, it became clear what the bang was: a crack across the window in the entrance hatch. Bad as that sounds, it wasn’t dangerous on the floor, since the entrance tube was always flooded during a dive, meaning the window was not a pressure boundary. It did, though, create a chance of being trapped at the surface. “If we couldn’t get out we’d be stuck in there for a few days feasting on Hershey bars.”

There is a sense of anticlimax about the bottom. No photos, since the landing had stirred up a cloud of sediment which didn’t disperse; and only 20 minutes on the bottom since they needed to surface in daylight. “It was like being in a bowl of milk. We didn’t get any pictures.” The highlight, instead, was Piccard sighting a foot-long flatfish, “like a sole or halibut”, which confounded scientists given the intense pressure on the ocean floor.

The journey back to the surface was smooth. “There was a sense of achievement. And some celebration: we worked like hell for almost a year to get to this place.” There was little carnival, though, 200 miles out at sea. “After dinner I was ready to have a nap.”

A period of celebrity followed, with a meeting with President Eisenhower; Walsh says he is “genetically not programmed for celebrity stuff” but appreciated the opportunity it gave to lobby for more support for this type of exploration. But it didn’t pay off: not long after the dive the Navy decided it was not safe to dive below 20,000 feet, so the Trieste became, and remains, a unique event.

For his part, Walsh says the motivation was not a record per se. “I was never driven to go deeper and deeper,” he says. “There was a singular goal out there and that was the deepest place in the ocean. Getting there required a systematic testing of the vehicle. Things broke, we fixed them.”

Nevertheless, down to earth though he is, there’s no escaping the frontier significance of the time. “The number of people that had piloted manned submersibles in the world you could count on one hand: it’s the days of Glenn Curtiss and the Wright Brothers when there were only two airplanes.” It’s just that perhaps when you go down instead of up, less people notice the significance of what you’ve done. “I’m writing an unauthorised autobiography,” he dead-pans. “The Right Stuff, The Wrong Direction.”

BOX 1: THE OTHER DON WALSH.

So what happened next after the Trieste program? “Well,” says Walsh, “a lot of people think I died.”

Such is the penalty for creating an historic event with so much of your life still to go. In fact, Walsh did plenty: he commanded a submarine, the Bashaw; served in both the Korean and Vietnam wars (“I think two per customer is sufficient for a lifetime”); gained three graduate degrees; worked in the Pentagon as an advisor on submarines; became the founding director of the Institute for Marine and Coastal Studies at the University of Southern California with the rank of dean (“universities are more rank-conscious than the military”); and built a successful consultancy, International Marine Inc, that continues to run from Oregon today.

But it’s the continuing exploration that sets the pulse racing, and Walsh has done plenty.

In 1971 Walsh first visited the Antarctic with the navy, as part of Project Deep Freeze, which involved inhabiting and running Antarctic stations on behalf of scientists. His efforts were so well appreciated that he has an Antarctic ridge, the Walsh Spur, named after him. “I really enjoyed it but I never thought I’d get back,” he says.

The opportunity to do so came when small expedition cruises began to grow in popularity, taking tourists to the Arctic and Antarctic; Walsh was approached to serve as an on board lecturer in the mid 90s and has now notched up 27 trips to Antarctica, 26 to the Arctic and five to the North Pole itself. Walsh (and his wife, Joan) were part of a non-stop circumnavigation of Antarctica on a Russian icebreaker in the 2002-3 season, only the 11th time the trip has been done.

He’s also dived in the Russian Mir submersibles on the Titanic, Bismarck and the North Atlantic Ridge, something born out of many years of cooperation with Russian submariners who were once very much the enemy. “On a North pole trip on a Russian icebreaker most of the engineering staff on this nuclear powered icebreaker had come from the Soviet sub service,” he recalls. “We would sit in the bowels of the ship and drink lots of vodka and talk about our adventures; they showed me periscope photos of the US aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk they had taken from their Soviet sub.” On one trip conversation turned to the fact that nobody had ever been to the real North Pole – under the sea, 14,500 feet beneath the ice cap. A plan was hatched with Mike McDowell, the Australian founder of Quark Expeditions, to do so using the Mir submersibles and a Russian mother ship.

“We needed three things,” he recalls. “We had to get money, the front end one-time cost of about $3 million; we needed to sell tickets to about 20 tourists to come along and make a dive after the explorers had gone; and the third was to get the charters of a nuclear icebreaker and a mother ship for the submersibles.”

For years, though, only two of the three would ever come together, and the Titanic and Bismarck dives came along as commercial operations for tourists and aficionados like Titanic director Jim Cameron in the meantime. “All these were placeholders, bookmarks; the real goal was the North Pole.” And then, in 2007, came bad news: the Russian government had decided it would be an all-Russian expedition. “They came in and took all our planning and hijacked the whole thing.”

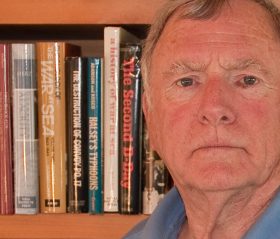

This clearly annoys Walsh but life is not so bad, living on his ranch deep in rural Oregon, surrounded by books in an office designed by his wife and apparently made up almost entirely by shelves. “Joan says that end to end they make 1,006 feet – the exact length of the Bismarck,” he says (among the many achievements of Walsh’s life is finding a wife who not only tolerates his adventures but knows to the foot how long the Bismarck is).

It’s an odd place, one might think, for a specialist in undiscovered ocean depths. “Simple,” he says. “I have bonded with my fellow man as much as I care to in this lifetime. My nearest neighbour is a mile away, I have a half mile salmon river on the far side of that pasture, and if more than half a dozen cars go by the front of the house during the day my wife complains about the heavy traffic.” Even the experimental biplane he built is up for sale in nearby Bandon. “I haven’t flown it for a while,” says the 78-year old. “I’m just too damn busy.”

“Now that I’m 78, it’s probably time to act my age,” he says. His immediate schedule – a host of engagements around Europe – doesn’t sound much like slowing down. “But in the polar regions you’re working out of the zodiac boats, helping passengers who’ve never been to these places before,” he says. “You don’t want this geriatric old fart stumbling around tripping over penguins.”

He and his wife talk about “a ritual burning of the parka, out in the yard,” to symbolise this end to the adventuring. It hasn’t yet happened. “But there’s got to be a last trip.”

BOX 2: WHY HAVEN’T WE GONE BACK?

In 50 years, the only other visitors to Challenger Deep have been remote-controlled submersibles: the Kaiko in 1995 and the Nereus in 2009.

Why have no humans gone back? Partly, it’s about money. “Science is primarily interested in data per dollar and since the 1990s ROVs [remotely operated vehicles] have proven themselves useful at trench depths,” says Peter Batson of Deep Ocean Expeditions.

“The exploratory desire is always balanced by difficulty, cost and safety,” says Captain Doug Marble in the Office of Naval Research – the division responsible for the Trieste dive 50 years ago. “Oceanographers have been able to probe the Challenger Deep by other means, such as acoustics, without going there in person.” In addition, the equation about human safety has changed since 1960. “I would guess that the intense, large scale activities of World War II and the atomic bomb prompted the realization that geophysics was ill understood for the needs of the time. Risks were undertaken [by humans] which today would be ceded to remote and autonomous systems for the initial steps.”

Then there’s engineering. Batson says: “The deepest trenches are about 11 kilometres deep, but cover only 2% of the ocean floor. So if you can build a manned submersible that can go six kilometers down, you’ve got access to 98% of the world’s sea floor.” This has influenced the design specifications of later manned submersibles, such as Japan’s Shinkai 6500, which can go to 6.5 kilometres. “Trieste’s deep-diving abilities came at a cost – it was huge compared to modern submersibles and was logistically difficult to operate,” Batson says. Instead it will be endeavour that takes us back: hence the most likely man to repeat Walsh’s feat is currently Jim Cameron.

Walsh is, if not bitter, then disappointed by the way things have gone and one senses a certain antagonism both about the US’s failure to keep pace with manned submersible technology, and with disproportionate spending on space exploration. Asked about the context of the 60s, when the space race was developing in earnest and Joe Kittinger was setting a high dive leap from a hot air balloon at the edge of space that still stands today, he prefers to highlight the achievements of submariners at the time: the Nautilus going across the Arctic Ocean under the ice cap by way of the North Pole; the Triton circumnavigating the world totally submerged. “When I met President Eisenhower I realized that he had only given personal decorations to three military persons in eight years,” Walsh says: himself, Bill Anderson of the Nautilus and Ned Beach of the Triton. “They were all submariners.”

“There is a lack of investment in studying the ocean compared to space,” says Walsh. “But we live here on this manned spacecraft called Planet Earth. Few of us are going into space. It’s entertaining, and certainly the son et lumiere of a space launch is formidable. What we do, one minute it’s there, the next minute it’s a cloud of bubbles. It’s not very exciting. But it’s very important.”