Discovery Channel Magazine: The Crazy Statue of Crazy Horse

Euromoney: Will SMX carve itself a niche?

20 September, 2010Asiamoney.com: Indonesia fever hits the markets

22 September, 2010Discovery Channel Magazine, October 2010

Picture Mount Rushmore, that most iconic of mountain carvings. Now take one of those 60-foot-high presidential faces and imagine that the sculptors had made it 90 feet high instead. And rather than just the face, imagine they decided to do the entire body – riding on a horse.

Imagine, too, that instead of carving it into the rock face, they decided to turn the entire mountain into the statue – carving it in the round, like a vast Rodin sculpture. Then picture doing it while refusing all state and federal funding, making it almost entirely the endeavour of just one family, moving at such a painstaking pace that after 62 years of tireless effort you still couldn’t say it’s more than a quarter done.

Welcome to the Crazy Horse Memorial.

To see the article is at ran in Discovery, click here CrazyHorse

Here, in the Black Hills of South Dakota just 30 miles down the road from Mount Rushmore, the Ziolkowski family – now in its fourth generation of involvement with the project – has been carving the world’s largest statue out of the granite of Thunderhead Mountain since 1948. It is perhaps the most audacious piece of craftsmanship ever attempted. With a planned final height of 560 feet, it depicts Crazy Horse: the iconic Native American hero, a Lakota warrior who fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Korczak Ziolkowski, a Polish-Bostonian sculptor who had worked on Mount Rushmore, was approached by local Lakota leader Henry Standing Bear – a cousin of Crazy Horse – to create a Native American equivalent to Rushmore in the 1930s, and once he began he never did anything else for the rest of his life. He died in 1982 after 35 years of ceaseless effort on the mountain. So today it is his widow, Ruth, who leads the work and who sits down with Discovery Channel Magazine to tell its story.

“I was only 20 when I got here,” she recalls. “Being 83 now, I think that’s relatively young.” Having crossed paths with Korczak and Standing Bear when they visited her Connecticut school in the late 1930s, she came to South Dakota in 1947 to see how they were doing. She never left. “Korczak picked me up in the railroad depot in Rapid City. To get here and see the mountain, with absolutely nothing done, no road coming in, no electricity, no water… Korczak always said it was as close to pioneering as you could come in this country.” They were married in 1950 and would raise 10 children in this wilderness.

Korczak really was going it alone. The Lakota who wanted the carving – “commissioned isn’t the right word. They had a dream and they sold Korczak on that dream” – had nothing to contribute to its creation. “In those days Indian people still starved to death on the reservation.” With no money, and what was clearly going to be the life’s effort of several generations, did they really believe it could be done? “Absolutely. Korczak could sell you the Brooklyn Bridge. He didn’t have a doubt in the world and I don’t have a doubt now.”

How do you start carving a mountain? You make a model (Korczak sculpted several, from 1/300th to 1/34th scale); then you measure the mountain in relation to the model; and then you remove the rock that doesn’t fit in order to get close to the surface you want to carve. That’s a lot of rock – 7.4 million tons by the time he died, and roughly the same amount since. For almost all of Korczak’s life, the job must have seemed more like mining than sculpting, starting out by dragging a single-jack up the 741 steps he had built to the top of the mountain, then drilling holes for dynamite blasts. For years, decades, there was nothing to see.

“But it was the little things that made a difference,” Ruth says. “When he started the first V-shape right in front of Crazy Horse’s forehead; getting the stairs built up the mountain; getting a compressor and actually having a piece of equipment. Even though you couldn’t see the difference you felt in your heart that you’d made progress.”

Things would have gone much faster had it not been for Korczak’s dogged refusal to accept state or federal funding, although many companies do make donations of equipment. “Working at Rushmore he learned a lot of things from [sculptor] Gutzon Borglum, whom he admired very much,” Ruth says. “He saw him have to go to Washington and lie to the politicians for four weeks at a time to get money. Korczak said: ‘I just can’t do that’.” Fundraising is a sophisticated effort now – a recent $5 million donation-matching gift from local businessman T. Denny Sanford has made a huge difference to the project’s pace and ambitions – but Ruth says the stance on government “makes more sense today than it ever did.”

The turning point for public recognition of the carving came after Korczak’s death – and in some sense because of it. Korczak had intended to start detailed sculpting not with Crazy Horse’s face but the horse. Ruth reversed that decision. “When Korczak passed on, there were a lot of people who didn’t think it would ever go beyond that: that we’d all just up and quit.” The face presented a much easier way to make visible progress than the horse. “His face is 90 feet, the horse’s head is 219 feet.”

Would Korczak have been supportive of the change? “Well if he wasn’t, I didn’t hear about it then. But I’ll hear about it later.”

The face itself took 11 years of work before its dedication in 1998. Opening just one eye took four months, 560 bore holes and 1,373 feet of drilling, with a range of techniques from hammers and chisels, feathers and wedges to a powerful and precise jet torch to finish the surface.

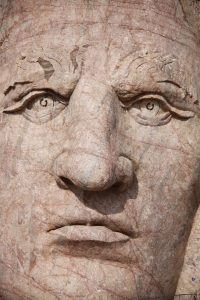

But it made a vast difference to knowledge of the memorial. “It proved to the world that we could carve the mountain, because there was Crazy Horse’s face to look at.” The decision may have saved the whole enterprise. Work has since turned back to the horse’s head, and the team has blasted and driven nine of the 11 benches required to allow access to the carving face. “I see now what it’s taking to do the horse’s head. If we’d ever tried to do that first, we’d have failed, because we didn’t have the money, or the backing, or anything to show that we could do it.” Today, up close, the face is extraordinary, imposing, glowering; as spokesman Pat Dobbs says, “his mood changes through the day. He can get real grumpy.”

Ruth’s entire adult life has been spent on the mountain and it has drawn in most of their children too. Seven of the 10 still work on the development in some capacity, and the other three live in the area; even a great-grandchild recently worked in the gift shop.

How would it be to grow up in such a family? “Well, not very different, because that’s all we knew,” says Monique, the second-youngest daughter, an accomplished sculptor and the project’s artistic advisor. “I thought everybody carved a mountain when I was growing up.”

There is only one question everyone wants to know the answer to. They never get it. “People say: well when’s it going to be finished?” says Ruth. “Well, in the first place, what’s ‘it’? [She means that Korczak’s vision was not just a mountain, but a university and medical centre too.] In the second place, what’s ‘finished’?”

“You’ve got a human being up there and his skin is finished. But how are you going to finish the horse’s hide? If you had to sit down and answer all these things before you ever started we’d still be talking about it.”

Impatience about progress is partly what drove the Sanford donation: he said he wanted his grandchildren to see the sculpture completed but that he wanted to see the horse’s head in his own lifetime. Is that realistic? “Oh I think so,” says Ruth, smiling broadly and with eyes bright. “He’s nowhere near as old as I am and I want to see it.”

BOX: MOVING A MOUNTAIN

The technology of carving Crazy Horse has moved on a lot since Korczak used to power a pneumatic jack hammer drill with a temperamental air compressor called Buda. Today a 10-man team, led by Korczak’s son Casimir, uses hydraulic drills mounted on tracks which use carbide steel bits to drill holes at up to 10 feet per minute. Dynamite is little used: instead small diameter water-gel or emulsion-based pre-slit products are placed in several hundred holes, which are then packed with small crushed stone, and blasts are set a few milliseconds apart using blasting cap detonators.

On the surveying side, Korczak’s original combination of tape measures, a theodolite and good old-fashioned artistic judgement have been replaced by a survey control system called a total station that uses an infrared beam to measure distances up to several thousand feet with accuracy to the nearest 1/1000th of a foot. Laser scanning is used to map the mountain into 15 million distinct points, allowing digital models to be built in engineering computers.

Daughter Monique, who was instrumental in the carving of the face, is closely involved here. “We scanned the mountain, scanned the model and put the two together to see how it best fits the rock,” she explains, in a cavernous studio dominated by a huge mock-up of the finished mountain carving. “Then you look at where you might have to bolt, where the seam lines are, understanding the rock mass. When you take the rock out from underneath it you want to make sure it’s going to stay there.” Though mundane and invisible to visitors, this is perhaps the single most important part in the memorial’s future.

One job that hasn’t changed much is mucking, or removing the blasted rock: a blast today products 2000 to 3000 tons of rock fragments from gravel to 10-ton boulders, but it’s still all got to be cleared out of the way with bulldozers. The material stays on site in a vast rubble field beneath the carving; otherwise it would take 200 truck loads to clear the rock from each blast.

BOX: KORCZAK ZIOLKOWSKI

Korczak Ziolkowski had a tough childhood. A Boston-born Polish American, he was orphaned at the age of one and grew up in foster homes. Although never formally schooled in it, sculpture was a release, and he made his first marble portrait – of a supportive juvenile judge – with a coal chisel. In 1939 a sculpture won first prize at the New York World Fair and he was asked to help Gutzon Borglum on Mount Rushmore. This brought him to the attention of Standing Bear and his Crazy Horse idea, although World War Two (Korczak landed on Omaha Beach) delayed its start.

Although Native American leaders requested the tribute – the 1948 site dedication was attended by five of the nine survivors of Little Bighorn – attitudes have changed over the years. Lame Deer and Russell Means are examples of prominent Native Americans who have stridently opposed the carving, considering it a desecration of nature and pointing out that a man who refused to be photographed (Korczak’s sculptures represent an interpretation of Crazy Horse’s identity) probably wouldn’t have wanted to be sculpted 560 feet high.

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s Native Americans, Caucasians or what it is, you never please everyone,” says Ruth. “One of the unfortunate things was the Standing Bear passed away early on in the project [1953] and we had to start all over again to make friends on the reservation, and that made it very difficult. But there has never been a doubt in the world it should be done.”

Relations have improved as other parts of the project had developed. Korczak envisaged a whole complex embracing a museum, medical centre, university – even a landing strip. Don’t hold your breath for an airport but the museum is impressive and detailed, and work is underway on the school dormitory, supported and ratified by the University of South Dakota. A scholarship fund gave out $180,000 last year.

But what prompted Korczak to devote his life to memorialising Native Americans? “I think some of it goes back to his Polish ancestry. If you look at Poland and see how they’ve been divided up and sliced off, it’s a little like what happened to the Indians as they were pushed west. And he was always for the underdog.” Standing Bear had another explanation. One day he found out that Korczak’s September 6 birthday matched the date of Crazy Horse’s death. “He figured Crazy Horse’s spirit hovered around the world waiting for Korczak to be born, and that was why he said yes.”