China’s rainmakers – Euromoney, April 2007

Shaukat Aziz, Pakistan prime minister: Institutional Investor, December 2006

1 January, 2007Green finance: cleaning up in China – Euromoney, September 2007

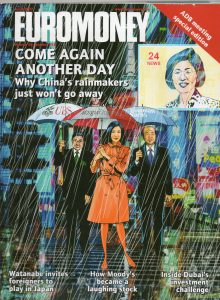

1 September, 2007Euromoney magazine cover story, April 2007

In the fluid and competitive world of China investment banking, new hires come and go, but occasionally one  comes along that really rattles the market. One such came in February when Merrill Lynch hired Margaret Ren, the former Citigroup China chief, as its chairwoman of China investment banking.

comes along that really rattles the market. One such came in February when Merrill Lynch hired Margaret Ren, the former Citigroup China chief, as its chairwoman of China investment banking.

This is a bold and surprising hire. Ren is arguably the ultimate rainmaker: bankers with such exceptional relationships that they can bring in big mandates for houses that might otherwise have no right to expect them. The daughter-in-law of former premier Zhao Ziyang, Ren proved her contacts and persuasiveness time and again at Bear Stearns and Citigroup. Her successes in getting Bear Stearns on to IPO and secondary issues for names like China Telecom and Guangshen Railway in the late 1990s, when the bank had no meaningful China investment banking presence to speak of, are widely considered the most extraordinary examples of leveraging relationships the China market has ever seen.

But she left under a cloud when sacked by Citi in 2004 over her behaviour in the IPO of China Life Insurance, a departure that has never been explained but is believed to have centred around allocation of shares in the IPO and a manipulated document submitted to the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Although subsequently cleared of wrong-doing by the SEC itself, her reputation was damaged severely.

The hire, like Ren herself, divides opinion. “Bizarre”, says a rival China head. “Excellent hire,” says a leading headhunter, not involved in her move. One banker: “Margaret without that family connection would have zero value in China.” Another: “She is without question the most effective China banker of her type the market has seen.”

The disparity in view, and the ferocity of attention, is because Ren’s move is about more than her past behaviour or ethical probity. It’s also because to many people, it represents a return to a style of China banking from a past and less sophisticated era: the rainmaker, or princeling, model.

The fashion these days is for banks to say they eschew the cult of the individual: that mandates are only won by houses with demonstrable excellence not just in coverage but execution, with industry expertise and a host of other skills beyond a well-positioned father-in-law or an ability to get a big meeting in Beijing.

Big China privatisations today are decided by committees with a far higher level of sophistication and transparency than has ever been the case before (see box). And besides, those elephant deals are running out, with Agricultural Bank of China the only landmark on the horizon; the big story today is private sector listings, as the companies born of China’s burgeoning entrepreneurialism seek capital. The people who run those companies couldn’t care less about government connections because they don’t have to.

Rivals look at Merrill’s hire – swiftly followed by a less controversial poaching, the recruitment of a rising China star, Rodney Tsang, from Credit Suisse – with some bemusement, seeing it as a step backwards, and wondering just how the bank can accommodate so many stars in one team. It already boasts Ehrfei Liu, one of the outstanding China bankers of his generation, as chairman of Merrill Lynch China; one market old-timer recalls him fondly as “leading the listing of China Southern Airlines when it was just a plane.” There is also already a China investment banking chairman, Wilson Feng, himself a well-connected individual (his father-in-law is Wu Bangguo, chairman of the National People’s Congress, who was in charge of state-owned enterprises under Zhu Rongji.)

Feng and Ren will work alongside one another and report both to Liu and to Sheldon Trainor, the head of Asian investment banking, a driven and strong-minded figure in his own right. They will have the further supervision of the man who led the hires, Pacific Rim investment banking head Damian Chunilal, who is also COO for Merrill Lynch Pacific Rim. As one banker puts it: “There’s an awful lot of egos in that place.” Another: “I don’t think Sheldon knows what he’s taken on.”

But Merrill is a bank enjoying great success in China, lead managing the record-breaking US$21.9 billion Industrial & Commercial Bank of China IPO late last year alongside a host of other transactions both lucrative and interesting. So these are not the hires of a desperate institution hoping to make up lost ground. So has Merrill, in taking a chance on what some see as damaged goods, just smarter and bolder than the herd? Or is it going to mess up a successful franchise with a hire that looks backwards rather than forwards?

To answer that, let’s first take a look at what the competition is doing with its staffing models. Because for all their protests of building teams not individuals, the fact is that the same dozen or so key figures, many of them best known for their connections rather than their execution skills, have been bouncing around different investment banks for years, with little new talent rising to the top. “Some say all the princelings are dead,” says a top Chinese headhunter. “I don’t think so. You’re just relying on smarter princelings.”

One perennially popular hire is Wei Christianson. Formerly at Morgan Stanley, she followed John Mack to Credit Suisse, then moved on to Citigroup to replace Margaret Ren, before being rehired by Mack barely a year into her stint at Citi to come back and run Morgan Stanley’s China team. This followed the departure of previous China head Jonathan Zhu to private equity firm Bain Capital.

Christianson prides herself on not only being adept at coverage and relationships, but at execution too. And like all big names in China, she denies being a rainmaker, a term that these days has clearly come to have negative connotations of ego and lack of franchise support. “I never considered myself a rainmaker, though I do think I have the capacity to bring in business and interact and make connections with senior officials and senior clients,” she says. “But I have that power because of the platform and because of the support the firm gives me.” Mainland-born, and a law graduate from Columbia University, Christianson also spent time at the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission before entering investment banking.

She argues that political connections are no more relevant in China than in London or New York, but recognises that in the mid-1990s “that was the only thing that was relevant. But this trend is changing. Firms are focusing on capable, very effective bankers who can build a relationship with clients quickly and sustain them. Those people don’t have to be the children of someone as was the case in the past.”

Morgan Stanley is clearly a force in China, topping ECM league tables in 2005 with lead arranging roles on the China Construction Bank and Agile Property IPOs before a more fallow year in 2006, but like all houses it does face challenges. One, a whole separate subject, is whether the bank must sell its stake in mainland investment bank CICC in order to build a domestic platform that gives it access to mainland securities. Another is the staff turmoil that accompanied Christianson’s return, with 12 departures from the broader China team, although Euromoney understands three were internal moves and three more at the bank’s behest. Jing Zhao, who moved to Citigroup as Christianson’s replacement, was the biggest name to leave. “The most important thing is we are hiring,” says Christianson. “We are a powerhouse, especially in capital markets transactions.”

When Zhao moved to Citigroup to replace Christianson, she moved to a house with surely the most troubled recent history of all foreign banks that hope to engage with China. Citi has found itself in strife three times: first back in 1999 when its handling of a pulled IPO for CNOOC effectively got it kicked off similar mandates for years; second when Ren, who was hired alongside Hong Kong’s own rainmaker Francis Leung in 2001 to correct that situation, left under such curious circumstances after having got Citi back into the field for big deals; and finally when, after reneging on a commitment to make a strategic investment in China Construction Bank, Citi found itself removed from the team to lead a share issue for the bank.

Citi’s most recent attempt to repair the business involves notably more low-key hires than Ren or Christianson. The bank has two MDs in China, both of them hired within the last year or so: Zhao, as head of China investment banking; Zhang Wendong, hired from UBS; and a third due to join from a rival in April. (Albert Ng was hired from PricewaterhouseCoopers but has already left again; numerous other MDs have at least some involvement in China.) People like Zhao and Zhang are admired individuals but neither are in the rainmaker mould of either of Zhao’s two predecessors.

Does this represent a difference in approach? Mark Renton, head of investment banking for Asia at Citigroup, says the model now “focuses on a team of senior bankers and plays to the strengths of the Citi platform.” He adds: “The marketplace is changing, and our sense is that relationships alone are not sufficient to deliver mandates. The client base in China is maturing very rapidly and becoming more sophisticated. Therefore you need to be able to front to those clients people who are very skilled bankers and relationship managers.” It is understood that Renton and Citi have tired of the star banker culture.

Citi ought to be a powerhouse in China investment banking because it has so much else going for it in terms of its broader China platform. When it opens in Hangzhou this year it will be Citi’s seventh mainland branch alongside 16 consumer bank outlets. It employs 3000 people on the mainland and is a market leader in areas such as forex, cash management, trade finance and securities services. It led a consortium that took control of the 502-branch Guangdong Development Bank, and it holds 5 per cent of Shanghai Pudong Development Bank. It is the only bank in this story to have been approved for local incorporation. Renton describes a multi-layered model combining the coverage team, industry specialists, the corporate banking platform, relationships through the local bank ownerships, and principal investment.

That’s quite a platform and Zhao, like her predecessors no doubt, believes it can be exploited. “The growing corporate footprint in China is being leveraged fully to complement the investment banking business,” she says. Citi believes its lead manager role on the almost US$2 billion China Coal Energy IPO in December demonstrates that it has again been rehabilitated; it also points with pride to its role on the first Sino-Indian JV last year as an M&A advisor.

It all ought to work, but then it ought to have been working for the last 10 years, and if Citi is ever to be successful it must be able to make this disparate range of talent work together. “You can’t judge a China team for at least three years,” says one headhunter. “They have hired very good people but are in the rebuilding stage.” Again.

Another house with a vast transactional platform and a modest recent history in investment banking is JP Morgan. By late 2005 JP Morgan’s lukewarm performance was drawing widespread criticism and is thought to be partly responsible for the removal of Asia chairman Ralph Parks last year.

If Parks did lose his job for a flaccid China practice, the timing was unfortunate, because 2006 turned out to be a record year for overall revenue in China, both in investment banking and more broadly. “We consider it to be a banner year, a watershed,” says Charles Li, chairman and CEO for China at JP Morgan, whose intriguing CV includes stints working as an offshore driller for CNOOC and a reporter at the China Daily. “China, for the first time on the investment banking front, was the biggest market in Asia Pacific – bigger than Japan, bigger than Australia.” The bank got onto the US$2.66 billion IPO for China Merchants Bank and a $1.98 billion follow-on for CNOOC. “People used to think: JP Morgan, great brand, great firm, but they somehow haven’t been able to pull it together in China. Now we have.”

Like Citi, JP Morgan’s franchise draws revenues from institutional broking, derivatives, and a host of wholesale banking services such as treasury, securities services, settlement and clearing. “It’s very significant fee generation business,” says Li. “They are almost like annuities. Once you have the mandate they’re there almost forever, so revenues are going to come in anyway regardless of having IPOs or not.”

JP Morgan doesn’t really have rainmakers, with its most well known name Fang Fang, the former CEO of Beijing Enterprises and now head of China investment banking. The house has a problem, though, with the loss of rising star Leon Meng, formerly Fang’s co-head, who like Morgan Stanley’s Jonathan Zhu has found the allure of private equity irresistible and moved to DE Shaw Group.

“It’s a very unfortunate loss for us,” concedes Li. “He is one of the strongest M&A bankers there is. Somebody with that combination of skills and experience and overall confidence is very hard to come by. But replacing people is not like it was 10 years ago when losing a top guy could shut you down for two years. The pool of candidates is much bigger now.”

Li, though, doesn’t think the market has moved as far as some do. “We are long gone from the model of magic children who can single-handedly make the rain fall,” he says. “It was bad for business, bad for China and bad for the people involved. But people who say we are completely out of that era are getting ahead of themselves. When you have very big [SOE privatisations] that still matters. Between a few giants [investment banks] the differentiation between them is so small that someone who has a special relationship or special child can still make the difference.”

One bank that has made a point of slamming the rainmaker idea whenever possible is Credit Suisse, whose departing Asia CEO, Paul Calello, has spoken frequently about his contempt for that idea. It’s worth noting, though, that Credit Suisse does have on its books Janice Hu, the grand-daughter of former party leader Hu Yaobang. Hu (junior)’s presence is believed to have done no harm to the bank’s success in getting on to the ICBC mandate. In fairness, those who have worked with Hu describe her as a capable banker regardless of family relationships, strong both in coverage and execution.

Hu is not the China chief, a role that is held by Zhang Liping (both are Merrill alumni), who was coaxed back to investment banking in 2004 after several years in the private sector. He oversees business lines including private banking and asset management – where the bank has a joint venture with ICBC – but in practice spends most of his time in investment banking.

A former Ministry of Communications staffer, Zhang was one of the first wave of China bankers. “I was called a rainmaker during the early 90s,” he says. “I was in the first group of pioneers working in China and have experienced the whole change of the approach to investment banking in this country. I don’t think I’m a rainmaker, at the end of the day business will be down to a team.” When Euromoney calls he has just seen a list of supposed rainmakers in another publication. “It was quite ridiculous. Some of the names listed had nothing to do with the transactions.” But, tellingly, he doesn’t think their role has gone forever. “In exceptional cases a person’s individual relationship may make a difference. I would say there is a 10 per cent chance for a mandate to be down to an individual’s relationship. The majority are awarded on institutional relationships.”

To put it in perspective, Zhang reckons that work on getting the mandate to joint lead manage the ICBC float last year began “four or five years ago. According to our memos we were one of the earliest banks pitching for the international IPO.” He sees every involvement with the bank since – including handling ICBC’s landmark NPL securitisation in 2004, then appointing ICBC as a custodian, and finally setting up the asset management joint venture – as part of the process of pitching for that mandate.

Like Deutsche (see box), Credit Suisse is a house perceived to be punching above its usual weight in China. Apart from ICBC, the bank joint led the US$9.2 billion China Construction Bank IPO in 2005, and, the same year, the largest sole-books IPO from the country to date, the US$648 million Shanghai Electric IPO. But the loss of private sector specialist Rodney Tsang to Merrill is a blow.

That leaves two houses of note, the heavyweights of China investment banking: UBS and Goldman Sachs. These stand apart from the herd not only for their recent dominance of league tables, but also because they are the only two houses able to get involved in A share listings, Goldman through its venture with Gao Hua, and UBS through its partial ownership of Beijing Securities. Goldman is ahead in this respect – it will rarely have been more proud of a domestic transaction than in its joint lead role on mainland insurer Ping An’s $5 billion Shanghai listing earlier this year – but UBS is now understood to have the approval to pitch for similar deals, up against domestic competitors like CICC, Citic Securities and Galaxy. To many banks, this is the future. “I see bankers in Hong Kong looking worried because their lunch is just being taken away from them,” one banker says. It will also dominate the way hiring selections are made in future.

Unquestionably successful over the long term, both houses scoff at the idea of rainmakers or any disproportionate contribution from the individual. But here, too, there are stars. At UBS, which recently lost Zhang Wendong to Citigroup, a recent heavyweight hire was Henry Cai (see ELIOT’S profile) as chairman of investment banking for China, who was certainly considered a relationship-based rainmaker in his previous role at BNP Paribas as co-head of investment banking for Asia. There, he had a focus on small and mid-cap sectors, but arguably lacked the franchise around him to make the best of it; the theory is that UBS gives him the platform to boost the bank’s participation in private sector transactions. He brought his team too, and it is notable that BNP’s joint venture with Changjiang Securities has fallen through since his departure.

“Rainmakers are always going to be important,” says Matthew Koder, joint head of equity capital markets for UBS globally, “but they’re going to be significantly less effective unless they’ve got people around them to support them and execute deals properly.” UBS has also previously hired George Li, son of former politburo member Li Ruihuan, suggesting it has as much respect for connections as anyone else. But whatever the rationale, it’s working: UBS ranked top of the ECM league tables last year despite playing no role in ICBC, quite an achievement.

Goldman, also not present in ICBC, ranked second, reflecting another success story. Goldman was the only major house to refuse Euromoney an interview, but it is known the bank sets great store on the 100 people it has on the ground in China, the track record it has established over time and now the opportunities afforded by its domestic venture.

But for a house that espouses the team message, it has given Fang Fenglei, who heads the Gao Hua venture, extraordinary power. Goldman had to use a complex structure to get its venture away, creating two separate entities: Beijing Gao Hua Securities (GH) and Goldman Sachs Gao Hua Securities (GSGH), each with different domestic licences. GSGH is owned 67 per cent by GH, and 33 per cent by Goldman; GS is owned 75 per cent by Fang and 25 per cent by the mainland large cap Legend Holdings. This means Goldman legally speaking holds no equity in GH, and instead has funded Fang with a $97.5 million loan. There are naturally believed to be suitably iron-clad covenants in place to protect Goldman’s interest but it’s hard to recall a greater display of trust in an individual than this.

So that’s the field: built on institutional strength, for sure, but still as full of big hitter individuals as it ever was. So is Merrill’s strategy out of step with the rest of what’s out there? Some think it is.

“It’s [Ren’s hire] basically reverting to how banking was done by these guys years ago,” says one observer. “One, she’s damaged goods, whether or not she was a scapegoat for broader problems at the China Life IPO. And two, the bulk of work is shifting into the private sector anyway. It doesn’t matter who you know, unless you know the chairman of the company.”

Damian Chunilal argues China affords a fourfold opportunity: government owned companies approaching IPO, listed clients that still have substantial state ownership, private sector entrepreneurs, and government or municipality clients. “You need different bankers for different clients,” he says. Ren will focus on state-owned clients, and Rodney Tsang on the private sector, where he was gaining acclaim at Credit Suisse.

But it’s not as if Merrill was short of personnel. One wonders what Ehrfei Liu and Wilson Feng thought of a hire that must surely imply they didn’t have sufficient connections themselves. Chunilal says Ehrfei Liu is to focus more and more on principal finance and private equity, and much less on day-to-day client coverage. “As he’s moved across, I needed to hire somebody, and Margaret was the right person to hire,” says Chunilal. And although Merrill has Catherine Cai doing coverage on the private sector side, Chunilal says that wasn’t enough for what he calls “the once in a lifetime event” of Chinese private sector wealth generation; hence Tsang’s appointment, and “we’re still understaffed in my opinion.” Private sector business already contributes more than half of overall China revenues, he says.

“I hired Margaret pure and simple because I liked her, I thought she was capable, I thought she had the right energy and content and would succeed,” he says. He met her two and a half years ago and decided quickly he wanted her on the staff; if the circumstances of her departure from Citigroup had any bearing on her appearance at Merrill, it was purely in delaying the hire because of the due diligence involved (on the way she was reputedly very close to joining Macquarie Bank, but that fell through). Chunilal says he “doesn’t see anyone as a rainmaker. This is about having a strong team in place.”

But there’s no question Merrill has a track record hiring a certain type of person. It has now had three senior people with family ties to Chinese political big hitters past and present: Janice Hu (now at Credit Suisse), Wilson Feng and Ren. One of the problems many people see with the hire is working out how she and Feng can work together, with their roles appropriately delineated; each has the same title. “We’ve always had more than one person cover the different areas of business in China,” says Chunilal. “The opportunity is big enough for more than one person to focus on each part of the business.” To many, the hire makes more sense if rumours that Feng has resigned are true (Merrill insiders deny them).

And the management challenge? “That’s my job, to lead and manage a team, and I like to think I’ve done a good job in doing that. With every hire you take a risk, there’s no question about it. But in the last three years we’ve got 90 per cent of our hires spot on.”

While nobody expects Ren to be a leader in the technicalities of deal execution, if she originates a few deals she will have done her job. And while family relationships have no doubt helped, there must be something more to her than that. Every profile of Ren mentions her father-in-law, but rather fewer point out that he spent the last 16 years of his life under house arrest, or precisely how that helps generate a mandate for a state bank or telco.

Whatever one thinks of the wit of the hire, there’s no denying Merrill has become a force in China. Recent successes include taking lead manager roles on state IPOs like ICBC, Shenhua Coal and China Power, private sector deals like Nine Dragons, M&A advisories like Lenovo/IBM and some quirkier transactions like the Asia Aluminium MBO, where Merrill took the company private, and financed the deal through a mixture of principal investment and a syndication of risk to sophisticated investors. It has done so with a stable team. “Stability of key personnel is essential. We haven’t had the merry-go-round some of our competitors have had,” he says. “Our China team has been rock solid and that stands in stark contrast to many of our competitors.” He’s right. But it remains to be seen whether the latest hires, perhaps the boldest of Chunilal’s time in charge, bolster that team or fragment it.

BOX: DEUTSCHE

Deutsche has promoted a mainland Chinese national to the highest level of responsibility of any foreign bank. Lee Zhang is head of global banking for Asia Pacific and chairman of Deutsche Bank for China. That means he not only oversees all of the bank’s operations for China but M&A advisory, equity capital markets (in an internal JV with the global markets team) and transactional banking in 16 countries.

When he was given the promotion, some saw it as an elevation in name but not in substance, expecting he would continue to focus on China and leave it to co-head Jonathan Paul to cover the rest of the region. But with Paul now retired, Zhang has the empire to himself, matching the great ambition he is said to have (some expect him to enter politics). Zhang says he spends one third of his time in China, one third in Hong Kong and one third in the rest of the region; he had been in Australia the week before Euromoney’s call and was due on a major pitch in southeast Asia the following week.

“Guys like Lee Zhang, China’s not enough for them,” says one headhunter. “They want to go global.”

Zhang is a fascinating figure. A charismatic and tough banker from China’s north, he took a curious route to banking, taking a Masters degree in plant science from the University of Alberta and working for Hewlett Packard in Palo Alto before moving to Schroders, then Goldman Sachs as chief representative for China, and on to Deutsche in 2001. A member of National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference – and one of only three members to work for a foreign corporation – he’s clearly connected, but Deutsche insiders cringe at any description of him as a mainland rainmaker. “It devalues his role a bit to say he’s a door opener in China,” says one, who also says Zhang is a stickler for deal execution rather than just being the coverage heavyweight he is depicted as being by rival banks.

Deutsche’s arrival on the China investment banking stage coincides directly with his arrival (although, to put it in context, Deutsche wasn’t really an investment bank anywhere until 1997). It’s an ascendancy that has perplexed competitors, wondering how it can be that a bank with no discernible presence a few years ago can have been lead manager on three of the five largest equity transactions in China since 2005 (ICBC, China Shenhua Energy and a Petrochina follow-on). Some complain that Deutsche has been particularly quick to play the national card, enlisting the Chancellor to lobby for mandates for the bank in the broader name of cross-border trade, but that’s a claim that enrages Deutsche insiders, seeing no difference between their leverage of the politics of nationality and Citigroup’s hiring Robert Rubin, or UBS Leon Brittan.

“When we first started my pitch was: we may not have a track record in China, that means we will work harder than everyone else, it’s important for us,” says Zhang. While it’s tempting to see Deutsche as a one man band given the synchronicity between Zhang’s arrival and the bank’s growth in presence, Zhang himself says: “I don’t think it’s ever been a case of: one individual delivers. At the end of the day it’s the firm, it’s the platform, it’s the team. Clients are not going to award a mandate to a bank that can’t execute it.” Deutsche has three top-level MDs below Zhang in China (Charles Wang, Amanda Lu and Yunfei Chen); one headhunter describes as “absolute rubbish” the suggestion that Deutsche lacks strength in depth in China, but does speak of Zhang’s “incredible presence. He’s well plugged in to the bank, too.”

BOX: MANDATE HUNTING

One of the biggest reasons people argue the rainmaker era has run its course is because of the growth in sophistication in Chinese mandate processes, especially in the big state-owned-enterprise mandates.

It would be a stretch to say the decision-making process is transparent, but many feel that it stands comparison with privatisation beauty parades elsewhere in the world. In at least two bake-offs, for ICBC and Bank of Beijing, people who pitched say they heard back from the selection committees with detailed feedback on their performance – in some cases down to their precise rank among the bidding banks, or the score they were given in particular areas of the pitch.

“When you see clients now making a big decision it looks like a real panel, with people sitting there doing the scoring,” says one senior banker. “They not only inform us if we’re in, they also give us the score.”

Wei Christianson at Morgan Stanley adds: “Rarely do you do a bakeoff anymore without knowing what’s actually going on. Clients will have a committee, often including regulators, and often academics, who are relatively objective since they have no political ambition. There is an argument that the real decisions are made behind the scenes, but I think the fact that more people are involved in the decision is progress.”

An environment like that makes it less likely that a relationship-driven outlier will turn up on the final ticket. “We are very infrequently surprised by the outcome on any deal,” says Matthew Koder, joint global head of equity capital markets at UBS. “We have a very good understanding of where we stand in any pitching or competitive process. I can’t remember the last time I was genuinely surprised at the outcome.”

Not everyone shares this view, though. “What we see, which concerns us, is we are lined up to do a sole lead role on an offering and suddenly another bank is there,” says one banker. “You say: what are you doing here? Then you find out one of their people is the daughter of the chairman of the issuing company. That’s a problem.”

And one oddity in the scoring system comes when a bank outside the top rank turns up on a mandate. Years ago it was reported that banks including Deutsche were going to make a formal complaint about the conduct of the Bank of China bake-off, but Lee Zhang denies that emphatically. “I am a great believer people should celebrate success but also be able to accept failure sometimes. Clients make decisions, there is a process, and we accept that.”

Acceptance can be begrudging, though, or just pragmatic. “The bake-off continues to be a sham,” says one senior banker. “That doesn’t mean it’s corrupt. It simply means that decisions are generally not decided at the bake-off. They are made before the bake-off, and the bake-off is there to provide the appearance of fairness and openness.”

To see this article in its published form, click here:http://www.euromoney.com/Article/1320801/BackIssue/51463/Why-the-China-rainmaker-just-wont-go-away.html